The Music of the Theatre Organ

Theatre organs were designed to be the most versatile musical instruments of their time. They were capable of rendering all types of music and of imitating most sounds of man, nature or machines. As we have seen, their initial purpose was to provide background music and sound effects for silent films. They were also played for featured solo segments in the evening's entertainment, and this became their prime function once sound films became established.

In this section we look at how they were used to fulfil these rôles and the types of music that were played on them.

Music for Silent Films

From the earliest days, silent film performances were anything but silent. Music was regarded as an essential enhancing factor, intensifying the dramatic and emotional impact of what was depicted on the screen. Whether that music was provided by an orchestra, a small instrumental combination, an organ or a piano, its skilful selection and performance could redeem an inferior film or heighten a powerful drama into a total entertainment experience.

Organs were used to substitute for or to supplement orchestras. When used solo, the organist enjoyed far greater freedom than the orchestral conductor to follow the action on the screen, as, unlike an orchestra, he was free to improvise and was not tied to a pre-chosen musical score. It was this flexibility, coupled with the huge range of tone colours at his or her disposal, which gave the organist an immense advantage in the skilled task of accompanying silent films.

Silent films are rarely seen these days, and there are few practitioners of their accompaniment - indeed, this has almost become a lost art. It is therefore worthwhile looking in detail at what that art involved.

In 1921, Fred Mumford, Musical Director at the Tivoli Theatre, Sydney, wrote an extensive article, entitled "Music and the Photoplay: Their Combination as a Means of Effective Entertainment", in which he answers at length the question "What is the right kind of music to play?". He writes from the perspective of Musical Director of a cinema orchestra, but the principles he espouses applied equally to organists:

To begin with, a Musical Director must have a lively imagination and a sure knowledge of the dramatic art, otherwise he will be at a loss to know what is required for his purpose. Dramatic music comprises many different movements known to the profession and stage directors as Plaintives, Agitatos, Hurrys, Mysteriosos, Themes, Melodramatic and by other titles, and to be successful one must know the meaning and use of these compositions. Take, for instance, the "Plaintive". This is music for use to describe love and devotion, and is used for all such scenes of tense feeling and poignant grief, and will always be found written in a major key. The moment such a movement is played in a minor key the character is altered and becomes totally unsuitable unless very great grief is shown on the situation when the major composition is unsuitable.

The "Agitato" is a style of music that at once suggests coming trouble of any description, and is usually started very softly and worked to business. This music is always in the minor key and of special character. Then comes "The Hurry". Good composition is always minor, and is good for fights, fire and mob scenes, storms and all situations that require weight behind them. the greatest effect is got by humouring the situation and closely watching the title on the screen. If the title denotes speech, drop to double pianissimo, and on the scene opening (if the fight or storm) is still going ahead, bring it to double forte as intensity requires, and always subside gradually for effect.

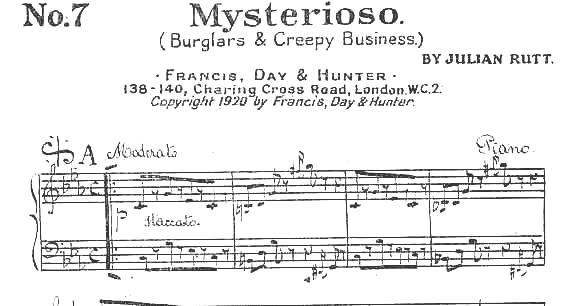

The "Mysterioso" is composed to denote stealthy movements, such as burglary scenes, creepy business, uncanny situations, haunted houses and motion picture exchanges. the mysterioso is usually written as a pizzicato for strings (often in unison), but the most effective movement is got by dividing the violins in tremolo in the high register, keeping the harmonies well sustained and a pizzicato movement (the melody) played by the 'cellos and basses in unison, but always in the minor key. A good example of this was heard in "The River's End" at the Tivoli on its initial screening. The character of Shan Tung, a Chinaman of particularly sneaky habits and a most unreliable and treacherous nature, required something special in the way of music to describe. I wrote a special motif for this miscreant, which was very successful. This number had to be Oriental in construction, yet give the necessary colour to the man's sinister influence. I wrote the music on the lines suggested above, and it fitted admirably, telling the story of the Chinaman's character at once. The audience, I am most sure, grasped it immediately, and the music assisted Shan Tung to dominate the scenes, as it was necessary for him to do.

Of course, it must be recognised by my brother musicians that this class of music can be had at will by selecting from his library music having these peculiarities. There are many compositions on sale that can be well fitted to the photoplay, and what is more the old Masters can be well represented with good effect if careful selection be made.

The "cueing-in" of Photoplays by the musical director is a matter that requires quick imagination and thought. The greatest trouble to be found by the director is the amount of "cut backs". A scene in progress requiring a certain kind of theme will suddenly change to another that apparently has nothing to do with the previous one that has been "fitted". The picture still goes on for another section or two and suddenly the "cut back" to the original scene takes place, and so on.

Now the only way to overcome these difficulties is to start out with a set purpose. My method is to study your chief characters carefully, and to treat them to the class of music that is suitable. Thus, whenever your character appears on the sheet you should be ready with your musical theme.

And one point more, and an important one - never, on any account, let the music get over the picture. This will be brought about if the music gets too noisy. There is no music in noise. The secret of success in "playing to pictures" is to keep well under the picture, let the screen be first and the music second. The audience may not audibly comment on the music, but their senses will be charmed just the same. This is the end which you must try to attain, and if successful you will have proved that music and the photoplay go hand in hand.

[Fred Mumford, Music and the Photoplay, "Everyone's", Sydney, 11 May, 1921, pp. 18-19]

F. Rowland Tims, organist at London's Capitol Theatre, wrote about his profession as follows:

The cinema organist must possess the art of showmanship; he is just as much a performer as the actor on the screen, and works with them for the success of the film. At times, a film seen in cold blood may be ineffective, but with the right musical accompaniment it can be put over as a success. At the Capitol I see my feature film several days beforehand in a private theatre, and usually spend one day in thought before I begin to work on the film. I have my own system of arranging my music library, and can instantly put my hand on a particular piece of music, according to the grade of "emotion" or "movement" in which it is catalogued. The music must create the atmosphere for the drama. the figures on the screen must be made to breathe.

The organist has to acquire a very extensive repertoire and to cultivate an imagination that will enable him to interpret rapidly changing scenes and screen action - one has to be prepared for anything. The outlook is kaleidoscopic.

It is not wise to repeat a piece of music until regular patrons would have forgotten to what scene or action its use was previously attached.

Besides feature films, one has to fit up comedies, cartoons, trailers (short scenes from a coming film), pictorials, news films, "Felix the Cat", educational films, cabaret films, fight films, etc. From day to day slight changes are made, and on these short subjects improvisation comes in useful.

Improvisation might be used in 5 per cent of feature films, especially for "flashes", i.e., scenes too short to set to fixed music, and for preludes and codas to extend an item where it is needed.

Provided that scenes allow at least a four-bar musical phrase, I believe in the closest possible fitting of every situation.

The cinema organist of today is one of the busiest of men.

My average day's work includes a rehearsal and trade show in the morning, say, from 10:00 to 12:45. the programme begins at 1 p.m., opening with a short organ recital at 12:50. The organ is used without a break until 11 p.m. or later. Occasionally there is a midnight performance, for the trade, beginning about 11 p.m. Besides these, there are special shows for the press (weekdays or Sundays), special rehearsals, viewing and fitting up the coming week's pictures, and marking cues for "changes" in all the music.

Allowing for the help of an assistant, a weekly deputy, and an orchestral organist, it will be seen that the responsibilities of a cinema organist are by no means light.

[F Rowland-Tims, The Cinema Organist's Work, article in "The Complete Organ Recitalist", ed. H. Westerby, Musical Opinion, London, 1927, p. 333]

How Mr Rowland-Tims applied these techniques is illustrated in a listing of some of the music he used to accompany the film "Her Man-o'-War", set just behind the lines in World War I. The love theme used was Savine's "Twilight Hour", and was used about nine times in all:

Film Scenes - Music - Composer

1 Village Scene - Prelude (Norwegian Scenes) - Matt

2 Big Guns Firing - Caesar - Beece

3 Underground Tunnel Found - Pizzicato Mysterioso - Langey

4 Two Men Creeping - Misterioso Dramatico - Fauchey

******

32 Germans Arrive - Nature's Prelude - Kempinski

33 Court Martial Scenes - Capriccio Italien - Tschaikowski

34 Girl Talks with Lover - Children's Intermezzo - Coleridge-Taylor

35 Girl Re-enters Court Martial - Pagoda of Flowers - Woodford Finden

36 Girl Kneels Before Picture - "Only a Smile" - Zamecink

37 Girl Hurries Away - Andante - Gabriel Marie

38 Girl Discovered at Wireless - p.39 - Wm. Axel

39 Men Burrowing Underground - Storm Music No. 10 - Zamecinck

40 Soldiers Enter - Prologue - Marie Ourdine

41 Girl Meets Lover - Love Theme - Savine

The music also included Wolstenholme's "Air du Nord", and Crackell's "Caprice in G Minor" for the organ.

[F Rowland-Tims, The Cinema Organist's Work, article in "The Complete Organ Recitalist", ed. H. Westerby, Musical Opinion, London, 1927, p. 337]

Not all organists and pianists were as skilful as Mr Rowland-Tims, who held the coveted F.R.C.O. diploma, nor were they as diligent or as resourceful in their choice of music. Most were, however, had a repertory somewhat larger than that of "Harpo" Marx, who played the piano for a short while in a silent picture theatre:

"When [Chico quit playing at a nickelodeon] Harpo got the job. But Harpo could only play one song on the piano which was 'Love Me and the World is Mine'. That didn't fit in with the average movie! He kept playing that all the time. Pretty soon the management got tired of hearing the same song. After all, if there are cowboys and Indians shooting at each other you can't play 'Love Me and the World is Mine'! So Harpo was fired. He lasted only a month."

[Julius "Groucho" Marx, "The Marx Brothers Scrapbook", written with Richard J Anobile, Darien House, New York, 1973, p.12].

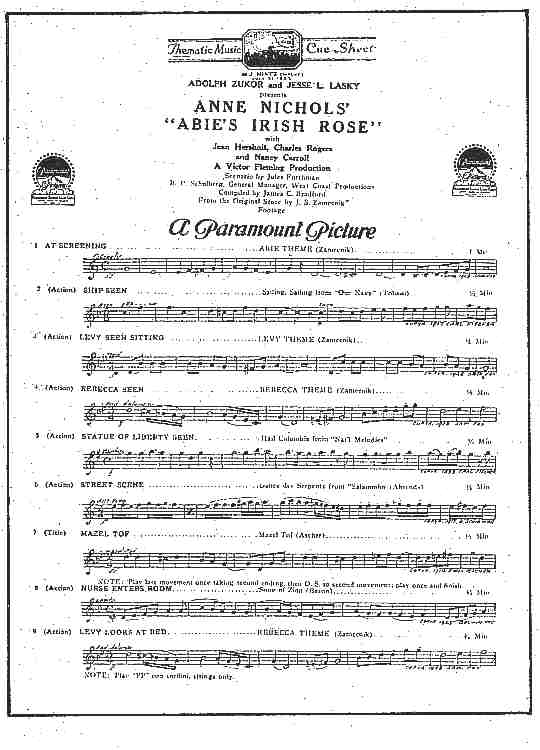

The film-makers were aware of that the accompanimental music had the potential to enhance or to destroy the impact of their product, and it was not long before many of the major films were distributed with cue sheets suggesting suitable music. A typical sheet for the 1910 Edison film "Frankenstein" read as follows:

At opening: Andante - "Then You'll Remember Me"

Till Frankenstein's laboratory: Moderato - "Melody in F"

Till monster is forming: Increasing agitato

Till monster appears over bed: Dramatic music from "Der Freischütz"

Till father and girl in sitting room: Moderato

Till Frankenstein returns home: Andante - "Annie Laurie"

Till monster enters Frankenstein's sitting room : Dramatic - "Der Freischütz"

Till girl enters with teapot: Andante - "Annie Laurie"

Till monster come from behind curtain: Dramatic - "Der Freischütz"

Till wedding guests are leaving: Bridal Chorus from "Lohengrin"

Till monster appears: Dramatic - "Der Freischütz"

Till Frankenstein enters: Agitato

Till monster appears: Dramatic - "Der Freischütz"

Till monster vanishes in mirror: Diminishing Agitato

[Quoted in "Sounds for Silents", by Charles Hoffmann, DBS Publications, New York, 1970, p.p. 14-15]

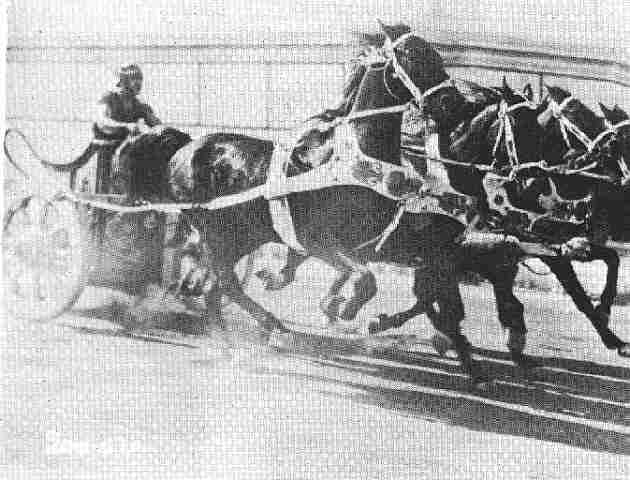

Although music was certainly an attraction to audiences, it was rare ideed for theatres to include details of the selections in their press advertisements, but in 1915, a theatre in Los Angeles did when showing "The Clansman", the original title of the film now known as "Birth of a Nation". Obviously much care and thought had been devoted to the musical side of the programme. One wonders how often at that time a musical director would view a film 84 times to select the music.

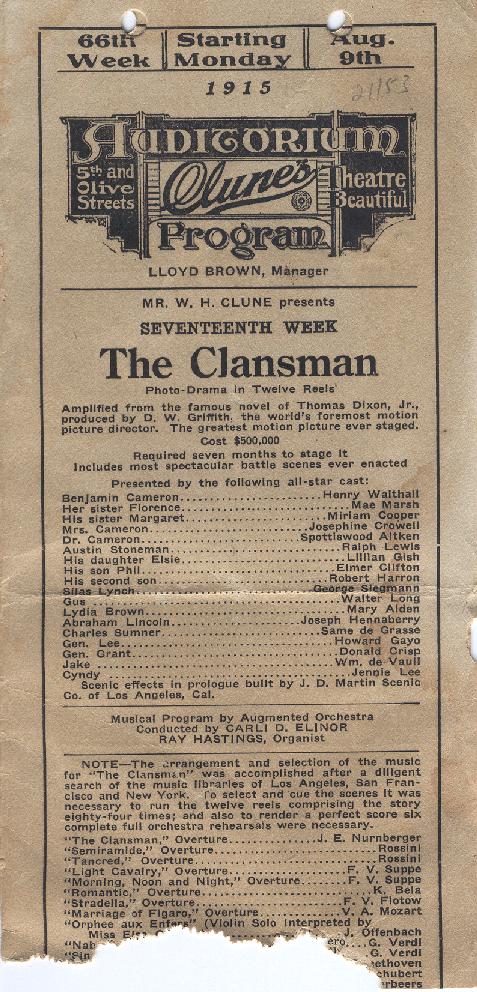

As time passed, the cue-sheets supplied became more imaginative and detailed, as illustrated by that produced in around 1920 for "Rose of the Wild":

No. Min. (T)itle or (D)escription Tempo Selections

1 1½ At screening 2/4 Allegro Farandole - Bizet

2 1¾ T-Rosamond English 4/4 Moderato Rose in the Bud - Foster

3 1¼ D-Harry leaves boudoir 2/4 Allegro Farandole - Bizet

4 1 T-For two months no word came 4/4 Allegro furioso Furioso No.1 - Langey

5 1¼ T-Then the survivors returned 4/4 Tempo di marcia The Rookies - Drumm

6 1½ D-Rosamund and Berthune 3/4 Andante sostenuto Romance - Mildenberg

7 3 T-After a time 2/4 Allegretto Canzonetta - Herbert

etc., etc.

[Quoted by E Lang and W West, "Musical Accompaniment of Moving Pictures", Boston Music Co., Boston, 1920, p.60]

By the mid 1920s, special scores were written for the most prestigious films, by composers such as Erno Rapée, Hugo Reisenfeld, Mortimer Wilson, etc. Some even incorporated silhouette pictures of the action on the screen. Many of these film scores incorporated melodies which soon became popular songs. Some songs still known today, such as "Smilin' Through", "Ramona", "Charmaine" and "Diane" began their existence as portions of scores for silent films.

The above extract is taken from the printed score that was provided with prints of "Birth of a Nation". The theme ("Amoroso") has since become a theatre organ classic under the title "The Perfect Song"

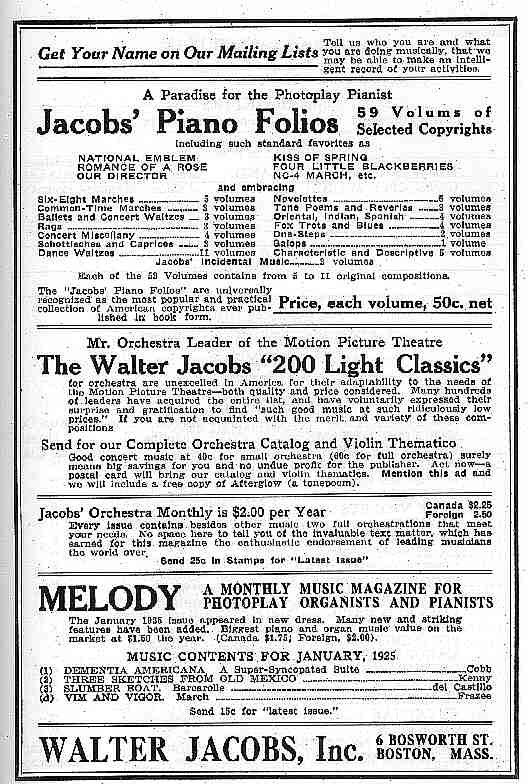

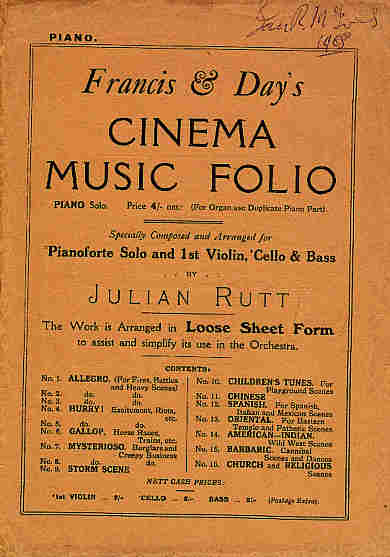

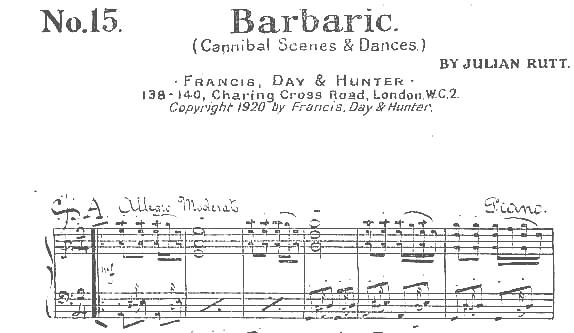

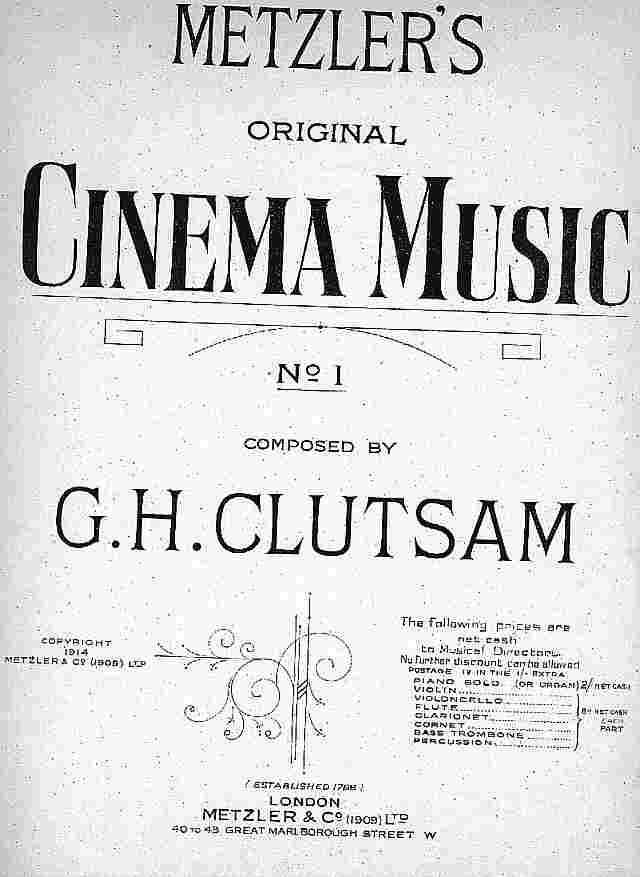

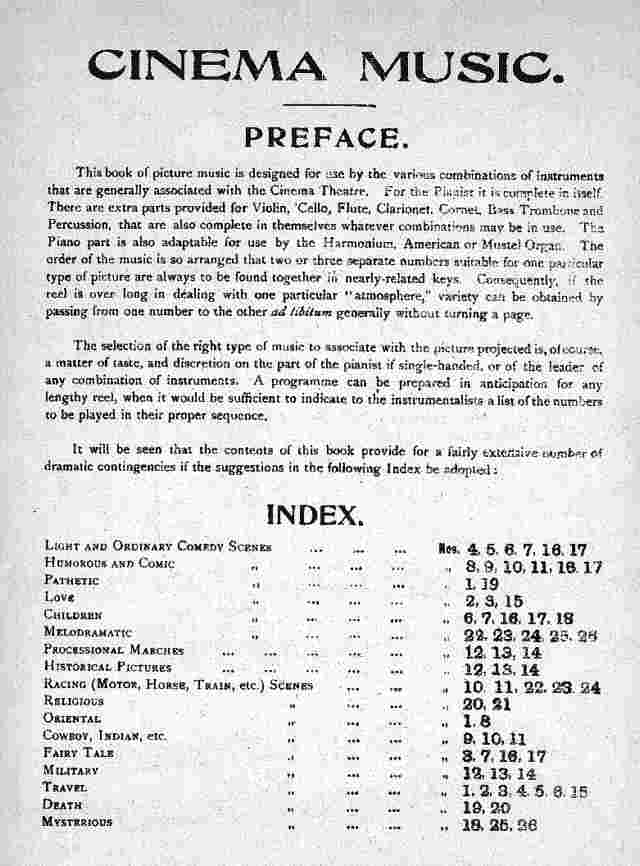

When a film did not have a score or cue-sheet, organists would have to turn to their own libraries. Many music publishers produced huge ranges of music suitable for films, often specially written for that purpose, and many lists were published in books and periodicals suggesting lists of music categorised by moods.

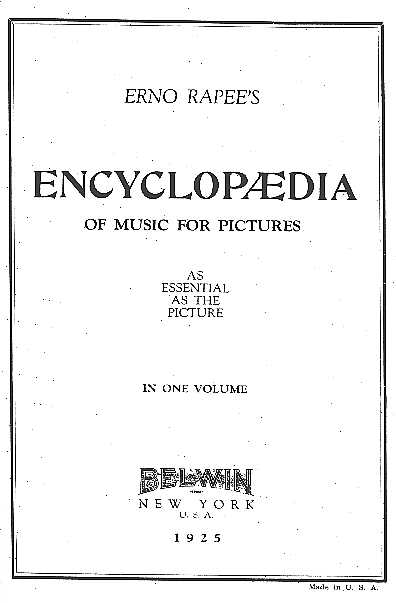

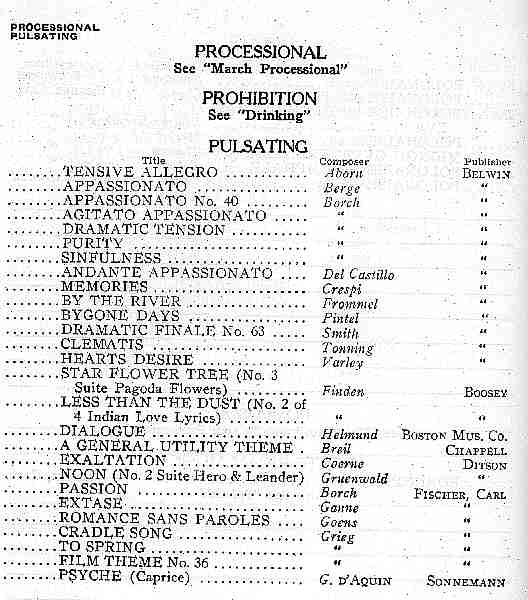

Perhaps the most extensive of these was Erno Rapée's "Encyclopedia of Music for Pictures", which contained over five hundred pages of lists of titles indexed by moods, with plenty of blank lines for organists to add their own selections as well. If an organist wanted music for an Abyssinian scene, he would be referred to Laurendeau's Shoe March and the National Song (which could be found in the Mammoth Collection). For "Pulsating" music, whatever that might be, two dozen titles were suggested, including three by Grieg [Erno Rapée, "Encyclopedia of Music for Pictures", Belwin, New York, 1925].

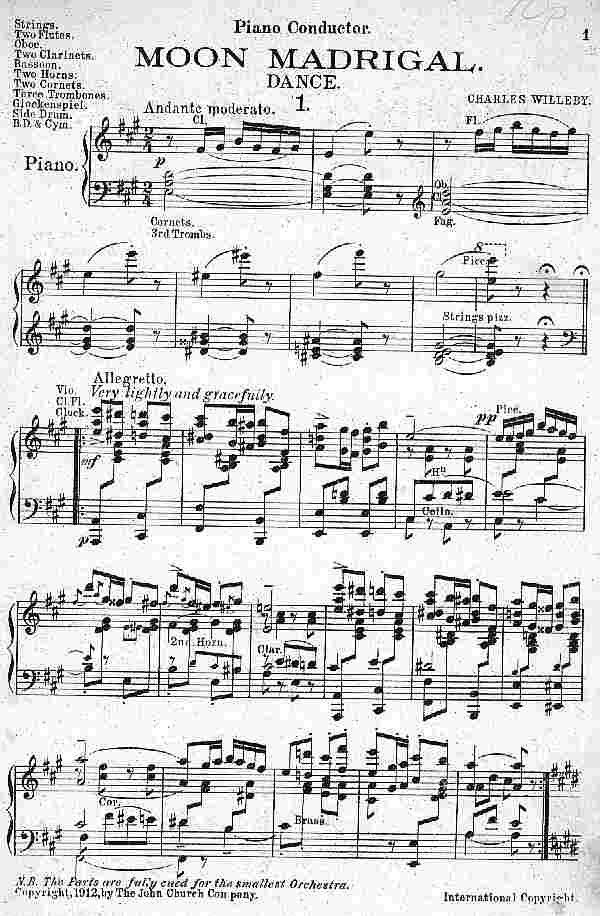

"Moon Madrigal" from "Cinema Gems - Concert Collection for Orchestra", published c. 1913

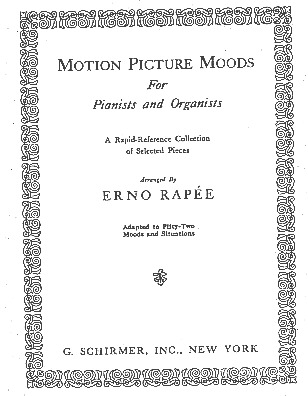

There could have been few theatre organists who did not keep handy at the console a copy of Rapée's "Motion Picture Moods for Pianists and Organists".

This weighty volume contains nearly seven hundred pages of music, not only grouped by mood categories, but with an index to 52 moods along the edge of each page , so that the organist could turn quickly to the appropriate page for the next scene. Much of the music was from classical composers (Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Elgar, Wagner and Bizet, to name but a few). Other pieces were written by such as Otto Langey and Gaston Borch specifically for silent film scenes. It even contains such esoterica as the National Hymns of Uruguay and Venezuela. There was hardly a scene which could appear on the screen which at least one piece in the book could not fit [Erno Rapée, "Motion Picture Moods for Pianists and Organists", Schirmer, New York, 1924].

Although today, the stereotypical silent film music seemed to comprise "Hearts and Flowers" for the romantic scenes and Rossini's overture to "William Tell" for action or chase scenes, the truth was that a very wide range of classical music formed much of the basis of film accompaniments, supplemented by drawing room pieces and popular ballads, and some music specially written, particularly for "creepy business", "hurrys" and fights.

"Keeping an eye on the cues was not always as easy as it sounds, because some of these scores were extremely difficult and often included whole movements from the great symphonies. As an example, I recall 'The Ride of the Valkyries' by Wagner lending thrilling realism to the scene in 'The Birth of a Nation' in which the riders of the Ku Klux Klan gallop into the night. I remember Tosti's 'For Ever and For Ever' being used as the love theme between Rudolph Valentino and Alice Terry in 'The Four Horesmen of the Apocalypse', and the lovely melody from Tschaikowsky's 'Romeo and Juliet' being introduced for the romantic sequences in other great silent pictures."

[Sandy Macpherson, "Sandy Presents", Home & Van Thal, London, 1950, p. 44]

We have seen above how F. Rowland Tims was a proponent of closely fitting the changing scenes on the screen. There were differing opinions on whether close-fitting or general background music was the more appropriate:

Some films are most incoherent. They seem to be composed, not on the principle of the gradual and skilful unfolding of the story, plot or theme, but of providing a succession of thrills - with little or no connection. To such a film the plan of close fitting or providing an excerpt from a different musical composition for every scene only emphasises its patchiness. If a musical accompaniment is only to provide a sub-conscious background, then, personally speaking, I find the perpetual changes of theme very disturbing, though to an unmusical person it may not be so.

I am inclined to think that the fashion for "close fitting" (as for jazz music) will give way to something more artistic. In the words of another: "Trying to intimately fit picture scenes, instead of broadly matching the story's motive, destroys continuity, and injects a disturbing restlessness into the atmosphere which an ordinary mortal is unable to escape" (American Organist, April, 1925). Another, Mr Diogenes Hunter, writes breezily: "It is the same old story; because we see something different on the screen, we must grab something different for the score. The idea is crazy. If the scene is so short that a piece won't fit it for several complete playings, then don't take such a selection - improvise on the theme if you like" (American Organist, August, 1926).

In the same number, Mr Henry Patterson Hopkins says "Modulating from one key to another brings up the subject of Improvising for Pictures. Some gifted musicians can improvise in an interesting manner for an hour or so." He, however, advises "a regular score to work from".

The use of Extemporised accompaniment for films has proved to be a subject of controversy. Dr Tootell, late of the Stoll Theatre in London, is an "out-and-out" advocate of extemporisation. Mr Quentin Maclean, of Shepherd's Bush Pavilion, is equally opposed to it, while Mr George T. Pattmann, of the Astoria Theatre, would use it "where an existing piece of music cannot be found just to fit the atmosphere; for some episode demanding special treatment, or as a bridge between sections." He uses also "motives or themes for some central idea or dominant character in the manner of a leit motif, but for the average cinema organist to extemporise artistically, consistently, regularly, every day, week in, week out, retaining freshness and originality - it simply could not be done. Little mannerisms and idiosyncrasies of the player would unconsciously become stereotyped and consequently monotonous.

[Herbert Westerby, "The Complete Organ Recitalist", London, 1927, p. 357]

Dr Tootell, mentioned above, published in 1927 a useful handbook, "How to Play the Cinema Organ, A Practical Book by a Practical Player", in which a complete chapter is devoted to the subject of how to extemporise a film accompaniment [Dr George Tootell, "How to Play the Cinema Organ", Paxton, London, 1927, pp. 87-103].

Naturally, when a cartoon or slapstick comedy film was being screened, the organist could give free rein to his or her imagination. The stock-in-trade was current or well-known popular songs whose titles echoed the action on the screen. For these films, classics were not generally very suitable, and jazz and rhythmic tunes held sway.

It was in comedy films in particular that the organist could really have fun with sound effects, either those built into the instrument, or those he or she could conjure up. A "prat fall" without a bass drum "thump" was like strawberries without cream. Reginald Foort described using a glissando on the tuned sleigh bells to create the sound of someone heaving a brick through a shop window [Reginald Foort, "The Cinema Organ", 2nd. edition, Vestal Press, Vestal, New York, 1970, p. 38]. Organists could produce sounds of snoring, dogs barking, trains, cars crashing, etc., most realistically, and some would even devise special mechanisms to produce special effects of their own. The most common of these was a piece of bicycle inner tube fitted over a high pressure wind outlet; this produced a flatulent noise of extreme vulgarity - in classical terms a "Voix Framboise"!

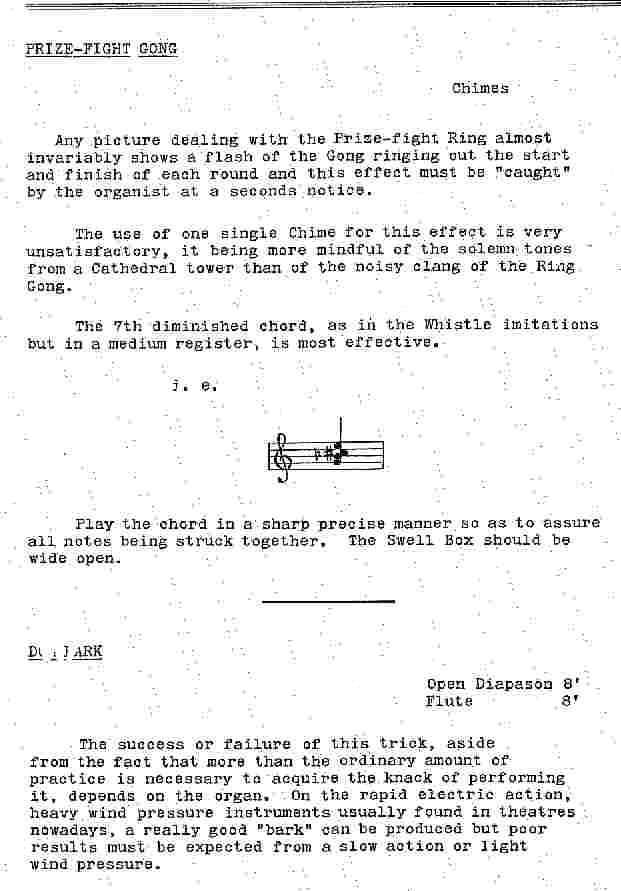

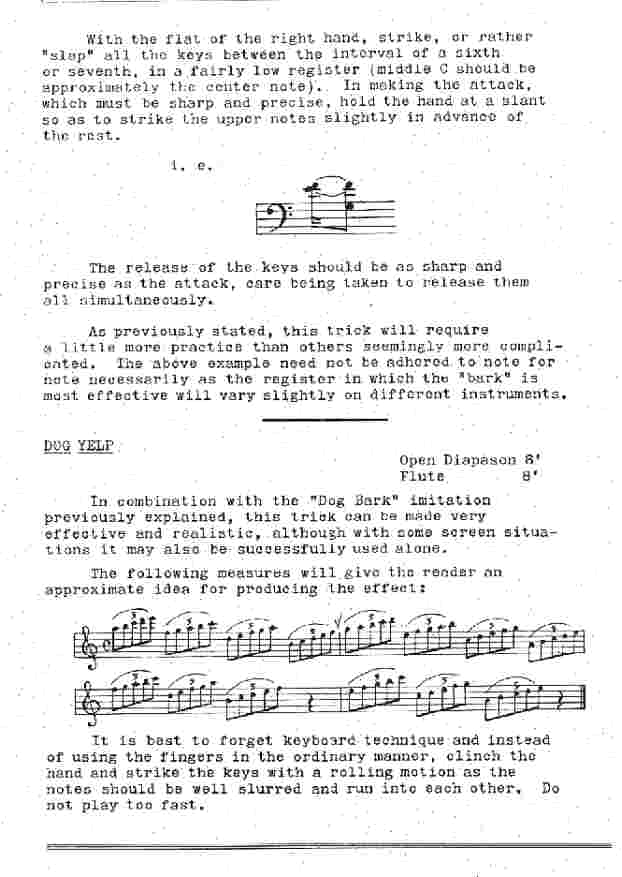

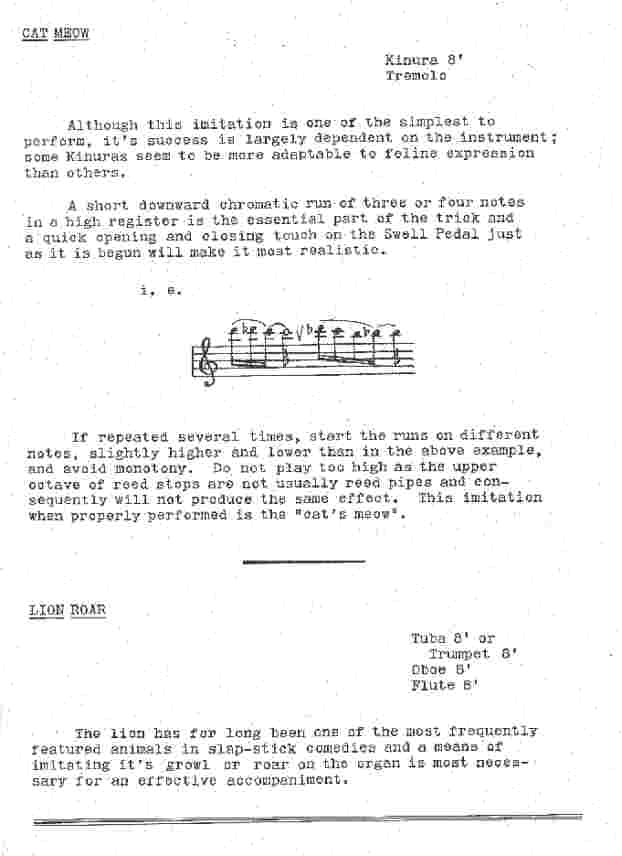

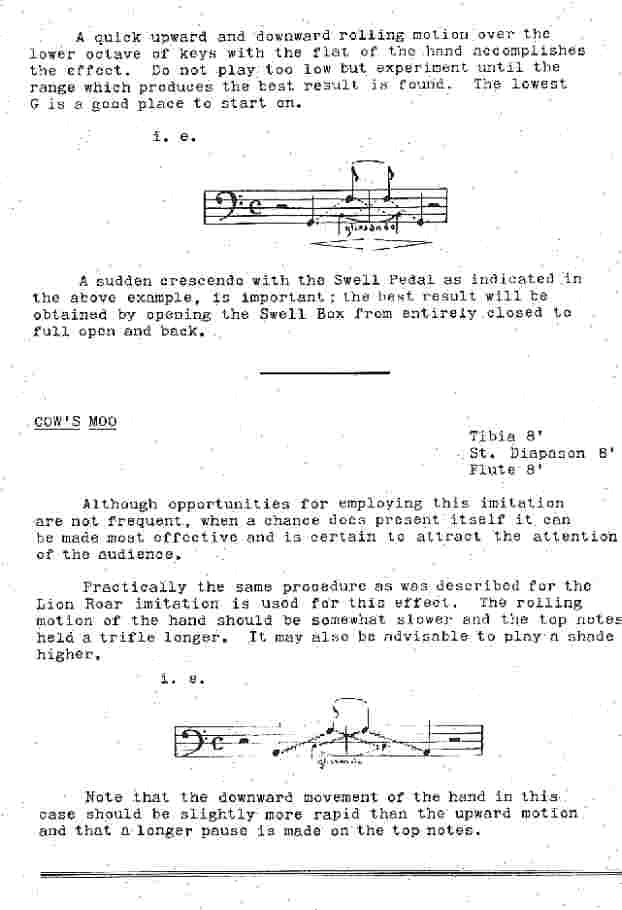

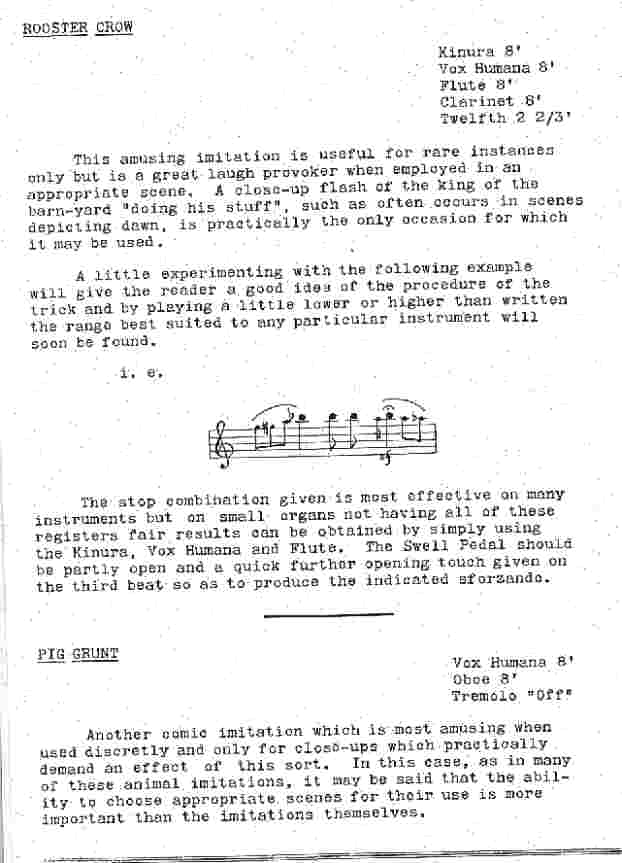

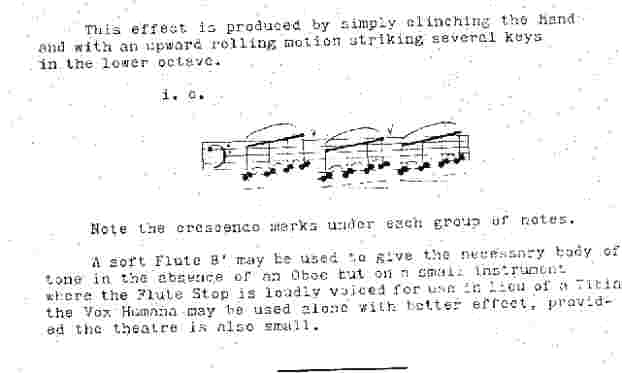

Organist C Roy Carter, of Los Angeles, compiled a booklet, describing in detail how to create the sounds of snoring, laughter, a kiss, a train, an aeroplane, thunder and rain, a steam whistle, a police whistle, a prize-fight gong, a dog bark, a dog yelp, a cat meow, a lion roar, a cow's moo, a rooster crow, a pig grunt, a cuckoo, bag pipes, a music box, a banjo, a hand organ, a harmonica or accordion and a typewriter!

"The importance and correct and artistic use of the effects and imitations possible on the modern theatre organ cannot be over-estimated. An audience will often be more favourably impressed by the organist who takes advantage of appropriate situations for putting in some clever trick or effect than by one who might possibly be a better musician but lets these scenes pass unnoticed. Remarks like 'Wasn't that a clever banjo effect the organist played for the Negro scene?', or 'Wasn't that rooster-crow imitation he put in, a scream?' are much more frequent than 'Didn't the organist play that Chopin Nocturne beautifully?'

It should be remembered, however, that a scene or a whole picture can be just as easily ruined by the indiscrete use or overdoing of these imitations. Do not be so anxious to put in tricks and effects that the audience is annoyed instead of amused. Good judgement for knowing when and when not to use an effect is just as essential, or perhaps even more so, than the ability to properly perform the trick. For instance, the Snore effect can be very funny or ridiculously crude according to the scene it is used for. In the case of a fat man snoozing on the porch on a hot summer day with the flies buzzing around him it would be funny, but the ludicrous effect if it were used for a scene in which the pretty young heroine is asleep in her elegant boudoir can be imagined. it is doubtful whether any organist would be guilty of such a crime, but there are plenty of organists that do things almost as bad."

[C Roy Carter, "Theatre Organist's Secrets", Los Angeles, date unknown (1920s)]

Organists did not always have the opportunity to preview the films. It was in situations such as this that the use of effects in particular could lead to problems. The hero might approach the heroine's front door, digit extended to ring the bell. The organist would then produce a resonant "Avon" ding-dong, only to see, to his dismay, the hero turn away, the bell unrung! I also recall an organist describing how in a scene the heroine ran to a church tower to ring the bells as an alarm, whereupon he produced a magnificent peal, only to see on the screen the title "But the bells did not ring"!

Such were the joys, and the pitfalls, of accompanying silent films.

Nor were matters much less exciting when the early talking films arrived. These and the primitive sound equipment were notoriously unreliable, and the organist would have to sit at the console for hours on end, bored witless, waiting for the moment when the sound broke down, and he would have to take over the sound portion until the apparatus could be cajoled into functioning again.

Interludes and Intermissions

It should not be imagined that the theatre organist's rôle was limited to the accompaniment of silent films. Most people under the age of about 40 would have little idea of what a night out at the picture theatre used to mean. Today, attendance at a multi-screen cinema "complex" means sitting in a depressing (albeit reasonably comfortable) room with a screen at one end, that in most cases is not equipped with curtains, let alone a stage. A single film is preceded by a few minutes of advertisements and previews of forthcoming "presentations", and that is the whole "show".

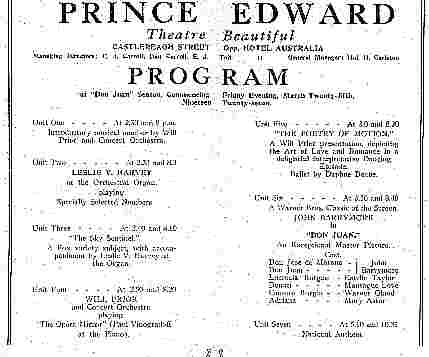

Things were very different in the heyday of theatre organs. There would usually be a "feature" film and another "supporting" film, together with a newsreel, cartoon, and, where there was an organ, a solo "intermission" played in the spotlight, and usually with the console raised on its lift to stage level, of perhaps fifteen minutes. Where there was an orchestra, that would also play a concert selection, frequently with the organ playing along with it. The largest Australian theatres, such as the Regents and States, would present elaborate stage shows and ballets, which the organ and/or orchestra would accompany.

The Regent, Melbourne, Organ and Orchestra

A contemporary report, somewhat supercilious (or maybe just tongue-in-cheek), appeared in "The American Organist" in the 1920s. It illustrates the kind of show that the American organists and musical directors who came to Australia to inaugurate the great picture theatres brought with them. The picture theatre described boasts "A symphony orchestra with chief conductor and his assistant, an organ (probably costing $500,000), with chief organist and his two assistants, a stage crew..." The house presents "De-Luxe shows and just-shows":

"The plain show uses only the lesser talent at the organ, while the orchestra lolls in the green room, while at stated intervals a de-luxe performance is given which is supposed to be the peak of the entertainment. the chief conductor enters the pit with a flourish and with a bow to the admiring flappers in the front row.

The chief organist is seated at the organ, the right foot placed on the grand crescendo pedal, the leader's baton (pronounced battongh) is poised aloft, and the overture (unit No. 1) is under way. This is ended with a storm of applause, the chief conductor bows, retires, and the assistant conductor takes charge during the News Reel, which is unit No. 2. After the President has thrown the first baseball, and all the battleships are launched, we come to unit No. 3. This is the ORGAN NOVELTY. A spot-light is turned on the chief organist, a slide is thrown on the screen announcing his name and the featured music number, which is - 'Why don't you kiss me when I pucker up my lips,' in six slides and two choruses played on the sleigh-bells, tibia and vox humana."

[Quoted by Herbert Westerby in "The Complete Organ Recitalist", London,1927, p.p. 324-5]

The demise of silent films was soon followed by the Depression years of the 1930s, and it was not long before the cinema orchestras were disbanded, although a few stage bands survived tenuously through that decade. Organs that were no longer needed to accompany films, became an entertainment feature in their own right. Their players were soon celebrities, their popularity enhanced through their being featured on the radio, both locally and nationally. Organ intermissions included elaborate slide presentations on screen to illustrate the music being played, or to provide the words so that the audience could sing along with popular songs.

Organists would tax their ingenuity to create each week a new presentation, some playing in the same theatres to the same audiences for twenty years or more. Novelty tunes would feature one week, light classics another. Some organists (with varying vocal talents and consequent success) would sing into the console microphone while they played. In the Sydney suburbs, organists would move around the Western Suburbs circuit's handful of organs on a rotating basis every few months, so audiences enjoyed the skills of a range of players over a year or two. Sometimes an instrumentalist, dancer or singer would add their skills.

In 1933, British organist Reginald Foort wrote an interesting and very relevant article about how he devised and presented organ interludes:

Some Ambitious Interludes

Ever since I started at the New Gallery in 1926 I have had great ambitions in the way of organ interludes, but in the early days of silent pictures and orchestras - and no console lifts - there were very few chances of playing interludes of any kind. The coming of "talkies", however, entirely altered the situation, and after an unfortunate period of uncertainty, ultimately made the cinema organ far more important than it was before, and provided admirable opportunities for all kinds of organ solo presentations.

There is no doubt that the real secret of successful entertaining from the organ interlude point of view is to devise some means of holding the eyes of the audience as well as its ears - to give it something to look at as well as something to listen to. Unless you go in for slides on the screen, this involves some kind of stage setting, and the simplest stage setting costs money. Now the cinema owner's outlook is that, at a vast capital expenditure, he has provided an organ, and he pays the organist what he considers a princely salary, and it is up to the organist to put up a show without further expense! However, I have been lucky. At the Regent, Bournemouth, I was fortunate enough to have a real genius of a stage manager - Mr E Nicklen, "Nicky" to all his pals - who has a real flair for manufacturing the most marvellous stage sets out of a few odd curtains and some bits of 3-ply. Our first really ambitious effort was a Hungarian Fantasy - in which I was joined by a pianist and a violinist - and for this we were provided by the management with real Hungarian gipsy costumes. I admit it felt a bit funny to go up on the lift dressed as a kind of Hungarian highwayman, but it certainly made the town talk and brought a lot of people to see us.

Nicky stayed on at the Regent, Bournemouth, after I left, but by great good fortune he rejoined me at the Regal, Kingston, soon after it opened, and it is here that we have been able to let ourselves go.

I never did believe in playing organ interludes in an amber spot in front of the house tabs: no organist on earth could go on holding the attention of virtually the same audience week after week under those conditions; I always use the full stage as a background to the organ console, and that gives an opportunity of exploiting Nicky's real genius, which is beautiful stage lighting. At Kingston we have no £50,000 lighting installation; ours is of the simplest variety and cost only a few hundred pounds, but I feel sure we could provide some of those big West End merchants with the surprise of their lives in the way of stage lighting. The management of the regal, Kingston, though, realise the box-office value of the organ interlude, and do not mind spending a little money on putting on a stage setting, but even so, our efforts up to date have cost almost nothing.

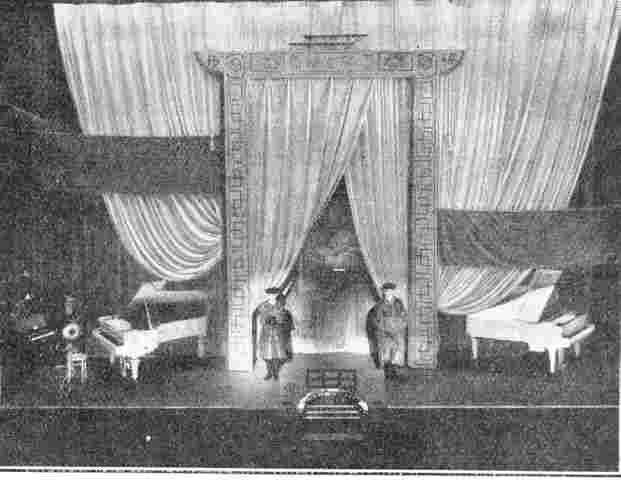

The Chinese set depicted here was put on as a prologue to "Shanghai Express." Wyn Lewis (my assistant) and I were rigged out at Clarkson's as Chinese mandarins and made up properly for each performance - putting on grease paint and "make-up" three times a day for a week really is a bit of a grind - but we thoroughly enjoyed the show, and so apparently did the audience. I believe the total cost of the entire set was about 4s 11 1/2d. We played a kind of symphonic arrangement for piano and organ of Ketèlbey's "In a Chinese Temple Garden," interspersed with snatches of the old pseudo-Chinese dance number "Shanghai."

An amusing interlude was in exploitation of the Lawrence Wright number "One Little Quarrel." This was originally devised by Sandy MacPherson at the Empire, Leicester Square, but, aided and abetted by the publishers of the number, who provided me with a singer for the week, I took the liberty of borrowing the idea, and a very successful interlude it made. The story was that I had had a letter from a fellow at Richmond asking me to play the number as he had had a row with his girl, and hoped the performance would lead to a reconciliation. I had the slides on the screen explaining it all, and of course the lad was sitting in the audience at each show and came up and interrupted me right in the middle of the interlude and offered to sing the chorus. To this day, I really believe some of our regular patrons are not quite sure whether it was genuine or a put-up job!

Probably the most artistic show up to the present was the Armistice presentation during the week of November 7th last year. There is a short called "Memories", which was made several years ago by British International Pictures at Elstree, dealing with the subject and incorporating impressions of a number of war scenes, and we used the first part of this. I started with "Land of Hope and Glory" with the screen tabs closed, and then accompanied the film with a medley of the old war-time songs as a background to the talking; when the war scenes began, we faded out the "sound" and I accompanied on full organ using the first part of "Rienzi" Overture. At a sudden silence, we brought in the sound again for the wonderfully effective speech - "These are the dead..." - and then as the film changed into a close-up of the Cenotaph, we faded it out and revealed a marvellous reproduction of the Cenotaph itself which Nicky had made, and I concluded the interlude by putting on a record of a choir singing "Abide with me," which I accompanied softly with church organ tone, finishing up with the softest stop on the organ on the house tabs slowly closing. It gave me the greatest satisfaction that at every performance the interlude was received in dead silence; just as I did myself, the audience sensed that applause would have been entirely out of place.

Our latest ambitious interlude was a Spanish fantasy. Our first idea was that Wyn Lewis and I should dress up as toreadors, but then I had the brain-wave of asking the professional in our ballroom to find a partner and dance a tango, so we worked out a medley of all the old Spanish dance numbers, "Valencia," "In a Little Spanish Town," "Lady of Spain," and so on, and right at the end, when the audience would have begun to get a bit bored, out came our two dancers in costume to dance a stage tango to the accompaniment of "In Santa Lucia."

[From "Cinema Organ Herald", June-July, 1933, p.p. 141-2]

Sydney critic Ronald Roberts expressed some views on interludes in 1939:

Last month I had something to say about my likes regarding the cinema organ. Now, I wish to point out a few of the things that do not appeal to me. Mainly, coloured slides, changing coloured spots, and to a certain extent, organists who insist on bursting forth in song whenever the opportunity permits.

A number of youngsters in the game have said to me "I wish I could sing." Why? I was always under the impression that the main function of an organist was to play the organ - not to sing. The cinema organ has a noble and ancient lineage - although some doubt it - and because of this there should be a certain amount of dignity about an organ interlude. An organist can always "get at" his public without making his session a vaudeville act. He should always be, first and foremost, a musician. Anyway, if the organist feels that a change is needed and that some song would fill the bill, wouldn't it be better to use some professional singer?

Now we come to slides. It is beyond me why some artists use these with their feature. Is it an admission on their part that they cannot hold their public without resorting to such aids? Is it that they have to take attention away from themselves in order to "get across"?

It is bad in this respect - it has the effect of making the music secondary to the slides, or at least I think so.

Spotlights that change their hues every few seconds irritate me. They distract my attention from the musician at the console. I don't mind a coloured spot - it's a pleasant variation from the dead white, but I feel that constant changing will quickly wear out the novelty.

The fact that an organist sings, uses coloured slides, etc., does not indicate, however, that he has no ability, but the point I am driving at is this, that these tinsel trappings could quite well be left out. Naturally, the organist feels that these aids are the safer course, and his judgement is to be respected - but I think that there could be a little moderation in the use of slides and lighting effects. As the directions say on a certain condiment; "Too much spoils the flavour".

[Ronald Roberts, With the Organists, "Australian Music Maker and Dance Band News", 1 May, 1939, p. 55]

Ronald Roberts had a regular column in which he frequently described what the organists in Sydney's suburban cinemas were playing in their interludes in the late 1930s.

November, 1939: "Clarence Black [at the Astra, Parramatta] played a group of Stephen Foster melodies quite delightfully and with a great deal of colour - as much as a five-rank organ would allow. His encore was a couple of the hits of the day to please the Saturday night audiences, who, generally speaking, preferred the lighter music to that in a subdued or serious vein."

December, 1939: "Jim Williams [at the Savoy, Enfield] played a special arrangement of 'Boomps-a-Daisy' à la Strauss Waltz, march and in practically every form except a fugue."

December, 1939: "Knight Barnett's [Palatial, Burwood] 'Rose selection' was a gen of subtlety and colour. He gave hackneyed numbers a new freshness, a new loveliness. I've heard a number of organists on the Burwood job, and still Barnett was able to thrill me with new tone colours."

December, 1939: "Of [Denis] Palmistra [who had featured a selection of gypsy melodies], need I say more? He goes into the byways of melody and seeks and finds a great many pearls of presentations. Palmistra favours the medleys, and always manages to play something which will please each section of the audience, be it slightly highbrow, middlebrow, or any other kind of brow. Palmistra is on of Western Suburbs [theatre circuit]'s best bets."

March, 1940: "Ron Boyce at the Vogue Theatre, Double Bay, pulled off one of the best presentations of the month with a patriotic 'Songs of Australia' in which he used a record of Debroy Somers' Band and played the Hammond organ along with it. Taking the audience around the Empire in song and with coloured slides of the Empire, it was a stirring show which concluded with the Australian flag fluttering in the breeze on a technicolor film clip."

March, 1940: "Bert Myers at the console of the Victory Theatre, Kogarah's little Christie, featured 'Gypsy Moon' , and during the interval he played a great version of 'Nola'. Some of the audience thought he 'Nola' would have been better as his features spot and 'Gypsy Moon' relegated to the interval chatter music scene. However, that's a matter of opinion."

March 16, 1940: Barrie Brettoner played his first show for Western Suburbs at the Savoy, Enfield. The composition of his selection is perhaps a little bizarre, but could not be accused of lacking contrast and variety... "Barrie Brettoner's opening presentation at the Savoy, Enfield, was a medley consisting of 'Rhapsody in Blue'. Light Cavalry Overture' plus a mix of 'Over the Rainbow' and 'Roll Out the Barrel' thrown in for good measure. It went down very well with a packed Saturday night audience."

April, 1940: Jim Williams at the State, Sydney, featured 'A Tisket a Tasket', then a current hit on record by Sidney Torch

May, 1940: "Owen Holland [Regent, Sydney] outdid them all and received rave notices for his presentation at the Regent of 'There'll Always be an England', into which he skilfully wove Elgar's 'Land of Hope and Glory' ... a thrilling musical experience."

[The above details extracted from Frank Ellis' series of historical articles "Down Memory Lane" in TOSA News 1984-86 that quoted many of Ronald Roberts' reviews]

To conclude our examination of the varied repertory and performance techniques by theatre organists in the 1930s and 1940s, here follows the text of a report by Ronald Roberts of an interview he had with organist Denis Palmistra in 1940, that sums up the issues and ends with words of sound advice:

"Denis Palmistra favours the Medley or Selection, wherein all manner of items are presented. In this way, he says, it is possible to please each section of the audience. It enables one to play for each of the 'brows', so to speak - high, low and middle. It is a well known fact that what one person admires another cannot tolerate. So, in playing a medley, it is practically certain that each and every one of the audience will hear at least one piece that he whole-heartedly enjoys. Continuing, he stated that the ultimate success of such a policy rest upon how a selection of numbers is made, a combination of taste and judgement being essential. For instance, it would be foolish to play a combination of three bright and noisy items together, or to go to the other extreme and play a bracket of quiet pieces. Variety is the keynote of success or otherwise.

Palmistra then discussed interpretation. the most vital thing, he said, was to see that the number being played received proper treatment. In this is is necessary to see that the character of the selection is strictly adhered to, and no radical departure made from it. Bound up in this question, also, is the point of musical training. He considers that a sound and very thorough mussical education is something no cinema organist can afford to be without. A solid background of such training helps a great deal in overcoming the trials which are part and parcel of the game.

From personal experience, he learned that the type of audience governs the choice of music to be played, and the type of program screened, in turn, governs the class of audience to be expected. One is not long on the console without learning the reactions of the people listening. It is not difficult to tell whether they are with you, against you, or just merely indifferent to your efforts.

I questioned him as to his attitude toward singing. His reply was that he has no wish to make the song the presentation, and that as far as possible he kept the proportion of song numbers down to about 15% of his total programme. But there is one big advantage in being able to sing - that is, it makes a more direct contact with the public and adds quite a personal touch to the programme. When the powers that be decide to change the organists around you might have to leave the organ but you can take your voice with you.

Summing up the position as regards presentation, he said: 'Always make it short and snappy, and always aim to leave the audience in the frame of mind that they haven't had quite enough'."