The Remarkable Talents of Jesse and Helen Crawford

It is somewhat difficult in these days when “celebrity” almost equates to notoriety to imagine that a theatre organist over seventy years ago could achieve world-wide celebrity status such that he would not only successfully tour overseas, but his endorsement of such varied products as hats, tobacco products and shaving products (and whose records for many years gave credit to Wurlitzer organs) would be sought to give cachet to those goods.

Jesse Crawford was the first theatre organist to achieve major celebrity status, although his daily life would probably have provided lean pickings for gossip-hungry pictorial magazines had they existed then in the form they do now.

Although he produced his best work before he left New York for California in the early 1950s, much of this material is little-heard as it mainly exists on well-worn 78 r.p.m. records, of which few have been reissued in CD or even LP format. This is unfortunate, for it was Crawford who, more that any other individual, shaped the playing styles of his contemporaries and, consciously or unconsciously, many of those who have followed in subsequent generations.

“The Listening Room” presents a comprehensive collection of his recordings dating from the mid-1920s to the mid-1940s, restored and enhanced digitally to reveal, in many cases for the first time, the hidden beauties and subtleties masked by surface noise and other distractions.

The accompanying notes concern mainly the background to the recordings and set the context in which they were made. For this reason, they are generally arranged in the chronological order in which they were recorded, which in some cases differs from the order (and even the years) in which they were released. Master/matrix numbers have thus been used, rather than record catalogue numbers, which are an unreliable guide in that respect, and moreover differ widely between the USA, UK and Australia, whereas the Master numbers remain the same. Even Master numbers can prove inconclusive, as there are at least two pairs of Crawford recordings (in each case one acoustic, the other electrical) both with the same Master number.

The 78 r.p.m. recordings do not tell the full story. One may wonder, for instance, how Crawford linked songs in his medley intermission performances. We can gain insight into more extended performances through the fortunate survival of a tantalisingly small number of recordings of broadcasts. Film and interview material add yet more depth to the picture. As there are several hundred items all told available it is necessary to be selective as to what to include, if for no other reason than that it usually takes upwards of an hour to restore just one side of a 78 record.

It is perhaps unfortunate that most of Crawford’s recordings that were still available in the late LP days were of largely public domain traditional music, that may have sold steadily, but lacks the flair and joy of much of his earlier material. Thus it is that for some people he has acquired the reputation for somewhat ponderous and unexciting performances. This is in no way alleviated by the fact that on many LPs that prominently feature his name only one track may actually be his playing, the others being by unmentioned performers of lesser status. Caveat emptor…

I have made a conscious effort in the notes to provide fulsome information without unnecessarily duplicating that contained in Dr John Landon’s definitive biographical work: Jesse Crawford, Poet of the Organ, Wizard of the Mighty Wurlitzer, published by the Vestal Press, Vestal, New York, 1974 - ISBN 0-911572-11-2. This is an essential work of reference to any student of Jesse Crawford and/or the theatre organ, as the two subjects are inseparably interlinked. If the information I have provided appears sparse, I recommend that you refer to that volume.

So far I have not mentioned Jesse’s wife Helen, who is an integral part of his story. Helen made only a few records, none of them as a soloist, and only five sides on pipe organ. It is fortunate that recordings of some broadcasts dating from the early 1930s and sponsored by a typewriter manufacturer have come to light, as these include wonderful solo performances at the Paramount Studio. These amply back the recollections of those who heard her and tell us that she was an extremely competent organist and could make the instrument sizzle; an ideal foil to husband Jesse’s less raunchy style.

Each recording has been individually restored, some being more worn than others. In each case, judgements have to be made as to how much acoustical detritus can be scraped off without harming the underlying music. In some ways the concept is similar to that of restoring a old master painting, although in this case, one is always working on a copy and can scrap the work and start over again, and again, and again… as has happened with more than a few of these examples. I have included both restored and unrestored versions of one of the Marsh 1924 recordings at the Chicago Theatre. Comparing these will reveal just how little fragile music there is under all the distracting noise. In most cases, though, particularly as the original recording processes improved over the years, it has been possible to achieve what I feel are fairly successful recreations of what was heard in the studios and theatres. I have in most cases given the results a stereo “spread” – if you don’t like that, then just feed one of the channels through your system. The spread is achieved by a time-offset, and does not use the out-of-phase devices that gave synthetic stereo such a bad name in the old days.

The records are played at the correct speed in each case, which in most of the earlier examples is 75 rpm, not 78. This correction restores not only the correct pitch but also the correct tremulant speeds as they were set. Every effort has been made to ensure that the sounds that result are as authentic and accurate as possible. Audio restoration software has improved out of all recognition over the past few years, so it may be that future developments will run rings around these efforts. But we shall have to wait and see. Unlike most audio software on the market, DC6 (http://diamondcut.com) one of the suites used (I use several different programs as suits the individual records) was specifically written to restore 78 r.p.m. recordings (the Smithsonian’s collection of Edison Diamond Discs), and is ideally suited to the material in this study.

Unlike a notorious LP compilation issued some thirty years ago, if there is a vocal refrain on the original recording, it will not be cut out; such butchery has no place in restoration.

Finally, no animals were harmed in the production of this website, which may contain traces of nuts. See your doctor if symptoms persist.

Draw up your chair, sit back and start clicking. It's going to be a long night...

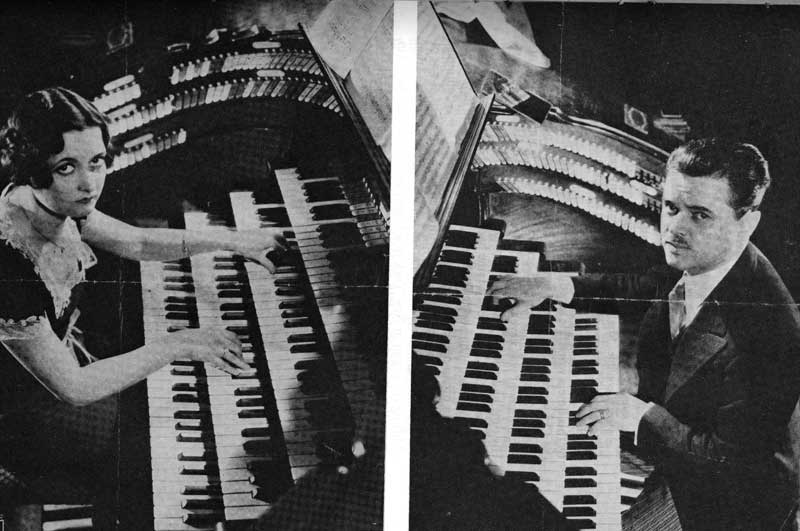

Ladies First -- Helen Crawford

Helen Crawford (née Anderson) was married to Jesse Crawford (see below) and joined him at the Chicago Theatre where a second console was installed so that they could perform duets, a practice that continued after they moved to the New York Paramount. They made a few duet records. Helen made no solo records, but accompanied Bing Crosby on two sides and played Hammond organ on a few records as a member of an orchestra conducted by her husband. Anecdotal evidence has indicated that she specialised in the more lively and rhythmic playing, a foil to her husband whose fame derived largely from his playing of ballads. That she was an accomplished and exciting player can be verified from recordings taken from broadcasts of the 4/21 Wurlitzer in the recording studio located in the Paramount building in New York City in 1931. In several surviving, although technically low-fidelity, recordings she plays solo medleys, accompaniments to vocalist Paul Small, duets with Jesse and reinforces a small studio orchestra. We hear three medleys, in the last of which Helen is joined briefly by Paul Small. She plays in both jazz and ballad styles, the latter mirroring many of the stylistic features characteristic of husband Jesse.

One of Helen's many compositions was a melody used for the song "So Blue". On this edition of the sheet music she appears as both performer and composer.

Click on the picture to hear Jesse playing this song at Wurlitzer Hall, New York City, on 15 March 1927 (Victor Master 38302). He is assisted by percussionist Joe Green

Hello, Beautiful – Truly – Wabash Moon – Tie a String Around Your Finger

I’m Alone Because of You – Blue Pacific Moonlight – Lonesome Lover

Thanks To You – Overnight – Walking My Baby Back Home (Paul Small sings for the first chorus)

Source: Royal Typewriter sponsored broadcasts, 1931.

All the above are contemporary popular songs. Note the contrast between the two choruses in “Walking My Baby back Home” when Helen approaches the tune with vigour after a rather laid-back first chorus with Paul Small.

Here are three fourteen-minute segments of Royal Typewriter broadcasts from which the above solos were extracted

First Broadcast Second Broadcast Third Broadcast

An Interesting Stylistic Comparison

From the surviving broadcast extracts we can make an interesting comparison between the playing styles of Helen and Jesse Crawford. They both played the song Tie a String Around Your Finger, and the contrasting styles and approaches are clear to see. Same song, same organ, roughly the same date:

Helen's version Jesse's version

Jesse Crawford listens intently to the wireless - perhaps Helen is on the air

Can't We Talk It Over - 21 December 1931 - Brunswick Master E37474 (vocal Bing Crosby)

I Found You - 21 December 1931 - Brunswick Master E37525 (vocal Bing Crosby)

Me, Myself and I - August 1937 - Hammond organ - Bluebird Record B7105A (with Jesse Crawford and his Orchestra - vocal Bob Murray)

Dancing Under the Stars - August 1937 - Hammond organ - Bluebird Record B7105B (with Jesse Crawford and his Orchestra - vocal Bob Murray)

It's the Natural Thing to Do - August 1937 - Hammond organ - Bluebird Record B7107A (with Jesse Crawford and his Orchestra - vocal Bob Murray)

After You - August 1937 - Hammond organ - Bluebird Record B7107B (with Jesse Crawford and his Orchestra - vocal Bob Murray)

Love Is On the Air Tonight - August 1937 - Hammond organ - Bluebird Record B7117A (with Jesse Crawford and his Orchestra - vocal Bob Murray)

On With the Dance - August 1937 - Hammond organ - Bluebird Record B7117B (with Jesse Crawford and his Orchestra - vocal Bob Murray)

Duets with Jesse Crawford at the Paramount Studio, New York

"Slave" console used for duets

Stein Song - 1 April 1930 - Victor Master 56814

The Moonlight Reminds Me of You - 2 April 1930 - Victor Master 56816 (voc. Paul Small) - Music written by Helen Crawford

Masquerade - 24 May 1932 - Victor Master 71742 (voc. Frank Luther)

Jesse Crawford

Jesse Crawford was the first theatre organist to achieve world-wide renown. He was one of very few organists whose individual influence on playing styles was immediate and enduring. His approach to the playing of ballads in particular and his use of fingered glissando techniques have influenced in one degree or another virtually all who have played the theatre organ since the 1920s. His playing was not, of course, restricted to ballads, as can be seen in The Listening Room selections, where sprightly versions of several songs show no hesitation in being brash and brassy with English Horn where appropriate.

1. Crawford at the Chicago Theatre - 1924 - Wurlitzer 4/27

Crawford’s first recordings were made in 1924, using an experimental electrical recording system invented by Orlando Marsh, who is seen above with his equipment on stage at the Chicago Theatre and Crawford at the organ console. At the time, the major recording companies still used an acoustic process, which, on the evidence of the recordings here, was far more satisfactory than Marsh’s system. Among the many faults in the system are the restricted frequency response, the internal generation of considerable background noise, and a number of unfortunate resonance frequencies, presumably within the microphone. In the restoration process, which has been in the nature of an archæological “dig” to extract the music from the noise barrage not only of years of wear and tear but also that created by the recording process and the theatre ambience, as many of these extraneous sounds as possible have been removed. The fragile musical content remaining has been enhanced as far as possible, but the inherent limitations, especially the minimal frequency response recorded, dictate boundaries to what can be achieved. Two items have been included because the song tunes were written by Jesse Crawford. An unrestored recording is alongside its restored version to illustrate the extent of unwanted and extraneous noise that has to be removed from these early electrical recordings.

More information on Orlando Marsh and his recordings may be found at http://www.mainspringpress.com/marsh_electric.html and http://www.mainspringpress.com/marsh.html

In a Corner of the World All Our Own - late 1924 - Marsh Matrix 233 - song written by Jesse Crawford. This is the lowest matrix number, so is most likely to have been Crawford's first recording

The World is Waiting for the Sunrise - late 1924 - Marsh matrix 432

The One I Love (Belongs to Somebody Else) – late 1924 - Marsh matrix 447

Old Virginia Moon - late 1924 - Marsh matrix 576 - song music by Jesse Crawford

All Alone - late 1924 - Marsh matrix 641

All Alone - unrestored 78 r.p.m. disc

Crawford contemplates a cigarette during his years in Chicago

2. Crawford at the Wurlitzer Store, Chicago 2/7 - 1925

The announcement of Crawford's first Victor records in early 1925 - He is shown at the Chicago Theatre console

It is believed that such success as Marsh achieved with his recordings (which appeared on numerous record labels) was largely due to Crawford’s Chicago Theatre discs, but it was not long before the venture failed. Crawford may have lost the money he invested in Marsh, but his records brought him to the attention of The Victor Talking Machine Company (hereinafter referred to as "Victor"), a prestigious company, who soon had him recording for them using the tried and tested acoustic process at the Wurlitzer Company’s showroom in Chicago, using a 2/7 instrument. Primitive though the recording system may have been, the results when scrubbed up, are far superior to those of the Marsh system, and produce quite an acceptable result.

Rose Marie – 17 November 1924 - Victor Master 31191

Somewhere a Voice is Calling - 17 November 1924 - Victor Master 31193

Old Pal - January 1925 - Victor Master 31650

I Wonder What's Become of Sally - January 1925 - Victor Master 31653

When You and I were Young, Maggie - January 1925 - Victor Master 31657

3. Crawford at the Wurlitzer Store, Chicago 3/15 1925 -1929

Stop list specifications for

Wurlitzer Store, Chicago

Wurlitzer, Style 260 Special, Opus 1099, 1925

|

Rank |

Pedal |

Accomp |

Great |

Solo |

|

8 English Horn 61p |

8 |

8 8t |

16 8 8t |

16 8 |

|

16 Tuba Horn 85p |

16 8 |

8 8t |

16 8 4 16t 8t |

8 4 |

|

16 Open Diapason 85p |

16 8 |

8 4 |

8 4 |

8 |

|

8 Tibia Clausa 85p |

8 |

8 4 8t |

16 8 4 2-2/3 2 16t 8t |

16 8 4 |

|

8 Krumet 61p |

|

8 |

8 |

8 |

|

16 String 73p |

16 8 |

8 8t |

16 8 8t |

16 8 |

|

8 Viol d'Orchestre 73p |

8 |

16 8 4 8t |

8 4 2 8t |

8 |

|

8 Viol Celeste 73p |

8 |

8 4 8t |

8 4 8t |

|

|

8 Oboe Horn 61p |

|

8 |

8 |

8 |

|

8 Quintadena 61p |

|

8 |

8 |

|

|

16 Concert Flute 97p |

16 8 |

8 4 2 |

16 8 4 2-2/3 2 1-3/5 |

|

|

8 Vox Humana 61p |

|

16 8 4 |

16 8 4 |

|

|

8 Vox Humana 61p |

|

8 4 |

16 8 4 |

|

|

8 Dulciana 73p |

8 |

8 4 |

8 |

8 |

|

8 Aeoline 61p |

|

8 |

8 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Chrysoglott |

|

C |

C |

C |

|

Harp/Marimba |

|

H Mt |

H M |

H M |

|

Xylophone |

|

Xt |

X |

X |

|

Glockenspiel/Bells |

|

G |

G B |

G B |

|

Chimes |

|

Ct |

C |

C |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Accompaniment to ... |

8 |

16 -8 4 |

|

|

|

Great to ... |

8 |

|

16 -8 4 |

|

|

Solo to ... |

8 |

8 |

16 8 8t |

|

Synoptic specification derived by Larry Chace from the stop list in John W. Landon's book, Jesse Crawford, Poet of the Organ; Wizard of the Mighty Wurlitzer

Wurlitzer installed the above instrument in the showroom of their store in Chicago in the late summer of 1925, where it replaced a smaller 2-7 organ on which Crawford had recorded a few sides for Victor using the acoustic process in late 1924 and early 1925.

It was to be December 1925 before Crawford returned to the store, to find a new organ and a new (electrical) recording process. Over the next three years he created a series of recordings of singular importance, which set his mark on theatre organ playing throughout America, as organists listened to them, and which were also strongly influential in other countries such as England and Australia , where they were marketed by Victor’s local associated companies, His Master’s Voice and Zonophone.

In America this influence was particularly pronounced as the time (1925-1927), coincided with a period of the prolific construction of new cinema palaces and the peak of theatre organ manufacture, with Wurlitzer completing organs at a rate of over one per working day, and the other manufacturers struggling to match output with orders. Along with all these new organs came the pressing need for organists to play them. Crawford’s records were available everywhere, and set a kind of universal paradigm for theatre organ playing, becoming what the public wanted and expected to hear, self-perpetuating as potential organists listened to these records and used them as patterns for their own playing. To such an extent had Crawford become an eponym of theatre organ playing that one enterprising organ company actually constructed a mechanical accessory so that an organist of lesser talent could emulate the way he would at times glide between notes using fundamentally the Tibia Clausa. They called it a “Drawl Effect”. Fortunately for theatre patrons who might have had this unleashed to assault their ears incessantly by misguided and minimally talented organists who could not achieve the effect using their own fingers, it appears that only a prototype “Drawl Effect” was constructed; but too late, as organs by that time were being supplanted by sound films, and production was not initiated.

When Crawford began recording this organ he was organist, with his wife Helen, at the Chicago Theatre. In 1926 he moved to the pinnacle of his career at the Paramount Theatre in New York ’s Times Square . If there were any doubt in 1925 that he was the world’s premier theatre organist, this was definitively dispelled when he arrived in New York . Victor did not like recording organs in theatres (although a few obscure in-theatre recordings were made, none by Crawford), and there was no studio organ available in 1926 in New York that would suit Crawford’s playing to the degree that Wurlitzer’s store organ in Chicago did, so for the next couple of years he travelled from New York to Chicago to make his records, unless time constraints were such that he was forced to use a two-manual organ in Wurlitzer Hall, New York. That he clearly preferred the Chicago instrument is evidenced by his continuing to return to it for his recording session whenever circumstances permitted.

Many of Crawford’s recordings from Chicago became best-sellers – Valencia was a particularly high-selling item. He even recorded new versions of Somewhere a Voice is Calling backed by Schubert’s Serenade, which he had recorded at the same location by the acoustic process using the earlier organ (see below).

The instrument itself is of great interest, in that its prime function was to demonstrate to potential clients the various sounds the Wurlitzer theatre, church and residence organs could produce. Hence it contains an English Horn, generally found on somewhat larger theatre organs at that time, and at the other end of the decibel scale, Dulciana and Aeoline ranks, more often found in church and residence organs than in theatre instruments. It is surely no coincidence that this organ contains the appropriate stops that match the requirements of the RJ roll-player; there is no evidence that one was actually connected to it, but if it were desired to do so, the organ could admirably demonstrate the capabilities of these rolls, aligned to a 2-7 instrument, and even make a fair fist of the larger Style R rolls and player, that could operate up to thirteen ranks from three manuals and pedals.

Assuming that the synoptic specification above is correct, some details are non-standard for the time; others may be seen as progressive. It would appear to be the first Wurlitzer organ in which the Tibia Clausa was available at higher than 4ft pitch (unless there higher pitches were later additions). It is shown at Twelfth (2 2/3ft) and Piccolo (2 ft) pitches. It was not long since the Tibia Clausa had been found only at 8ft pitch, and its availability on the Solo at 16 (TC), 8, 4, 2-2/3 and 2 ft pitches marked a new concept in theatre organ design that was soon to be echoed in the larger instruments built for the Ambassador, St Louis (where it appeared a 1-3/5ft pitch as well) and the Paramount, New York. The Tibia was now ready to play a much more prominent rôle in the make-up of the sound of the theatre organ than it had in the past.

The inclusion of the quieter Dulciana and Aeoline ranks would have been serendipitous for Jesse Crawford, who always paid great attention to the accompaniment parts of his arrangements. It can be heard clearly in these tracks that he was careful to obtain a balanced contrast in both tone colour and volume between melody and accompaniment parts. He makes use of stops such as the Quintadena to create interest as well as contrast, to which subtle rhythm patterns are then applied. The specification does not note the presence of pizzicato, but there is evidence of its use, especially in Mary (What Are You Waiting For?) .

Other unusual features of the specification, which differs quite markedly from the standard Style 260 design are the proliferation of inter- and intra-manual couplers, the inclusion of a Krumet to “cover” for both the Kinura and Orchestral Oboe ranks normally included and the omission of a Saxophone. The normal powerful 16ft wood Diaphone extension of the Diapason is replaced by a 16ft String bass. Whether this was done to suit the microphone or just to be in balance with the room is not known. A Style 260 Diaphone would have been useless for recording, as its frequencies would be too low to be captured by the recording apparatus, but it might well have shaken the recording head off the wax. At least with the string, there was a chance that some of the pipes’ harmonics would make it onto wax. However, in the recordings made, it is clear that 8ft basses provided the substance of the pedal for recording purposes.

The electrical recording process was still very much aleatory when Crawford arrived to start his first recording in December 1925. He had previously had some experience of microphones when Orlando Marsh had made some pioneer electrical records of him at the Chicago Theatre in late 1924. The recording quality of these discs was in many ways worse than the then standard acoustic process that used an exponential horn to focus sounds onto the cutting head. Apparently, Crawford’s discs were Marsh’s top sellers, but this was a relative term, and they brought little direct return on the money Crawford had in vested in Marsh’s system. In terms of his career, he was an established recording organist when contact was first established between himself and the Victor Talking Machine Company, and this could have given him a significant advantage in launching his recording career.

He was the only theatre organist for years to appear playing a theatre organ on Victor records (some other record masters were made of different organists, of which a few were released, but not on the Victor label). The only other entertainment organists of note who recorded for Victor (including “Fats” Waller and Sigmund Krumgold, both of whom stood in for Crawford during his holidays when he was at the Paramount , New York ) did so at the Estey organ in their studio at the old Trinity Church , Camden , NJ . Millions of Crawford's records were sold. Precise (audited and reliable) sales figures are not available for the period he recorded for Victor, but the eighty-or-so discs he made were pressed and sold around the world, and today still turn up in bric-à-brac shops and on markets such as e-Bay, with remarkable frequency, up to 80 years later. Some idea of the contemporary popularity of his records can be gauged from the following comment (that refers only to those copies sold in America on Victor’s Black Label, and not those pressed overseas):

Other hits by Victor's most popular scroll-label stars—Jesse Crawford, Paul Whiteman, and Gene Austin among them—averaged sales of a quarter-million copies. The extremely common Crawford-Goldkette recording of "I'd Love to Call You My Sweetheart" (Victor 20257) is typical of this category, selling 261,698 copies. Alan Sutton: The "Million Seller" Fallacy: A Reappraisal of 1920s Record Sales, http://www.mainspringpress.com/millions.html

Being a brand new system that Victor was keen to get up and running as soon as possible, it is hardly surprising that problems were encountered when attempting to capture on wax through the primitive microphone the complex sounds produced by a Wurlitzer theatre organ, even one as well-suited as this one. The recordings show how the recording techniques developed and were improved as each session arrived. Notable in the earliest records are systemic problems with quieter ranks that have a complex degree of harmonic development, the fourth (tierce) harmonic being particularly prone to run amok in the microphone. Vox Humana, strings and colour reed sounds vary in their harmonic content and volume on disc from note to note, depending on the microphone’s response to the frequencies involved. Originally, the surface noise when the disc was reproduced through the low-fidelity acoustic gramophones of the day, would have masked them, but once that background patina is carefully scraped away, these strange phenomena become apparent.

Fortunately, as time passed, these problems were resolved and eventually disappeared. However, for a long time it was a matter of experimentation to decide what stops could or could not be used on recordings, and organists using large organs were frequently reduced to selecting from considerably reduced palettes of “record-friendly” combinations. Matters were no better where classical organs were recorded, and the problems there were so extensive that in the music press of that time one frequently encounters complaints that recording companies made a great job of recording theatre organs, but classical instruments sounded dreadful on record, and asking why this had to be so. It is readily apparent that the Tibia Clausa, and in particular the sensuous example on this organ, perfectly suited the recording technology of the time, as its lyrical tones transferred perfectly to wax in the hands of the man who had elevated its status to that of the archetypical theatre organ sound.

There is little to be gained by my describing the music played – those for whom this site is intended will need no commentary. I have selected the more lively of Crawford’s musical pastels in preference to an overload of waltz-ballads, and have included a number of personal favourites. What are You Waiting For, Mary? was a personal favourite of the late theatre organ historian Ben Hall, and I also have a great liking for it. When the restoration of Baby Feet was done, there was no way those glorious tibia sounds were not going to be included. Meadow Lark was the first Crawford record I ever owned, at the age of about twelve. I was already familiar with his name through Reginald Foort’s The Cinema Organ, and my copy of this classic Crawford disc (issued in England by HMV) eventually became worn-out at about the time I found another copy in a junk shop. So those had to be included. Most of the other items virtually chose themselves, and I am happy that the selections provide a fair and enjoyable sample of his recordings on that rather special organ, played with his exceptional touch of genius.

Valencia - 30 May 1926 - Victor Master 35079-4

I'd Love to Call You My Sweetheart - 1 October 1926 - with Goldkette's Book-Cadillac Orch - Victor Master 36438-3

Meadow Lark - 5 October 1926 - Victor Master 36446

At Sundown - 28 June 1927 - Victor Master 390663

Baby Feet Go Pitter-Patter - 30 June 1927 - Victor Master 39068

El Faisan (The Pheasant) - 16 August 1927 - Victor Record No. 80110A (sold only in Latin America)

Secreto Eterno - 16 August 1927 - Victor Record No. 80110B (sold only in Latin America)

Somewhere a Voice is Calling - November 1927 - Victor Master 31193

Note: this is the same Master number as the 1925 version (issued on Victor 19521), but is both different and an electrical recording. Matrix 31193 is stamped into the shellac of both records, this version being issued on Victor 21207 in November 1927. Both versions were also issued in the UK on HMV label; again both issues are stamped 31193

Just a Memory - 2 November 1927 - Victor Master 40800

Dancing Tambourine - 1 November 1927 - Victor Master 40805

Mary (What Are You Waiting For?) - 2 November 1927 Victor Master 40809

I Can't Do Without You - 20 May 1928 - Victor Master 45400

The Dance of the Blue Danube - 20 May 1928 - Victor Master 45405

High Hat - 20 May 1928 - with Larry Gomar, xylophone - Victor Master 45404

Just Like a Melody Out of the Sky - 23 May 1928 - Victor Master 45407

4. Crawford at Wurlitzer Hall, New York 1927-28

Wurlitzer Hall, New York

Although Crawford travelled on several occasions from New York to record at Wurlitzer’s Chicago showroom, which by then had been equipped with a 3/15 organ, his duties at the Paramount Theatre did not always allow this, so he cut a relatively small number of sides in Wurlitzer Hall in New York, using a 2/8 instrument..

"During the years of our acquaintance, the only time I ever heard Jess use vulgar language was in reference to the two-manual Wurlitzer in the New York store. Despite other opinions, this was only a Style E with the usual two stock tremulants

-- Main and Vox. Crawford was obligated to use this facility because the train trip to Chicago was too costly and time-consuming with his New York Paramount Theatre duties. This store organ turned out to be an interim venue prior to the 1929 studio organ in the Paramount Theatre office building. Eventually, Crawford managed to finagle a regulator and tremulant for the Style E Tibia. The New York Victor engineers were, however, unable to cope with the live acoustical characteristics of the store studio. There are no 16' pedal tones on those recordings. Only the 8' Trumpet was used. This interfered, of course, with most attempts at artistic registration -- a gruesome fact that annoyed Crawford no end and brought on the aforementioned vulgar language. I must say that I admired his restraint for I might have been tempted to use even a more vivid and socially unacceptable vocabulary." George Wright:.Straight Talk About Crawford, November/December 1995 issue of the ATOS journal, Theatre Organ.

The above would, prima facie, appear a fairly strong condemnation of the Wurlitzer Hall's organ, were it not that the evidence of history and of the following recordings reveals a different story. The Wurlitzer Hall organ was a Style F 2/8, which had four tremulants (Main, Tibia, Vox and Tuba), and did not have a 10" #2 Trumpet, but rather a 15" Tuba Horn. More extraordinary is that George Wright apparently did not listen to the recordings, in which it is quite obvious that Crawford did not rely on the "8ft Trumpet" (which it did not in any case possess), for his pedal basses. Although 16ft Pedal is not apparent, as the recording system at that time did not successfully handle frequencies as low as 32Hz, that would not have registered, neither was it in any of his contemporary recordings, and indeed, it was some years before this was achieved.

The evidence of the entirety of Crawford's recordings indicates that his memory was incorrect (when talking at least twenty years post hoc), or that George Wright misunderstood his reference, as the comments align exactly to the first Victor recordings that Crawford made using the Style E 2/7 Wurlitzer (with the characteristics described) at the Wurlitzer Store in Chicago in November 1924 and January 1925. These recordings were made using the acoustic process, the frequency response of which would not accommodate even an 8ft fundamental (64Hz). It was therefore necessary to use the Trumpet in the Pedal, as its range of harmonics could be recorded and would provide the semblance of an 8ft bass. That this was done can be clearly heard in the examples of those recordings included in The Listening Room. It was common practice in many acoustic recordings for bands to use Sousaphones or Tubas in place of double basses, for the same reason that the Trumpet stop was used to provide the pedal bass in Crawford's acoustic recordings.

So it is that through a case of mistaken, or rather misremembered, identity, perpetuated by one who either didn't listen to, or who inexplicably failed to take note of, the evidence of the recordings, that the Wurlitzer Hall organ's memory has been maligned unjustly. It is time for these recordings to be given the hearing they deserve and for the slight of history to be removed from the instrument.

Just a Bird’s Eye View of My Old Kentucky Home – 21 January 1927 - Victor Master 37730 - (whistling by Carson Robison)

Blue Skies - 21 January 1927 - Victor Master 37731 - (Piano – Milton Rettenberg)

So Blue - 15 March 1927 - Victor Master 38302-1 (music by Helen Crawford)

Song of the Wanderer – 16 March 1927 - Victor Master 38303 (Vibraphone - Joe Green)

What Does It Matter? - 16 March 1927 - Victor Master 38305

5. Crawford at the Paramount Studio, New York 1929-1933 - The Victor Years

6

/

/

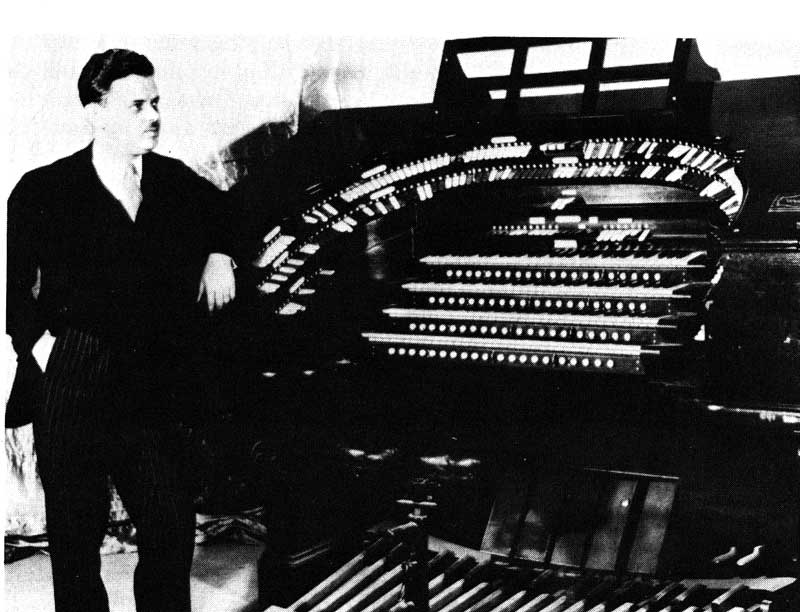

Crawford poses at the console of the organ specially designed for him to record and broadcast – recording studio, Paramount Building, New York

The organ recorded most by Crawford was the special 4/21 Wurlitzer in the recording and broadcasting studio located in the Paramount Theatre, New York.

Paramount Building, New York, recording

studio

Wurlitzer, opus 1960, 1928 (first used 1929)

4 manuals, 21 ranks

|

Rank |

Pedal |

Accomp |

Great |

Bomb |

Solo |

|

8 Tuba Mirabilis 73p(ipes) |

8 |

8 8t |

16 8 4 |

16 8 |

8 |

|

8 English Horn 61p |

8 |

8 8T |

16 8 |

16 8 |

8 |

|

8 Trumpet 61p |

8 |

8 8t |

16 8 |

16 8 |

8 |

|

16 Tuba Horn 85p |

16 8 |

8 8t |

16 8 4 |

16 8 |

8 |

|

16 Open Diapason 85p |

16 8 |

8 4 8t |

16 8 4 |

16 8 |

8 |

|

8 Horn Diapason 61p |

8 |

8 |

16 8 |

. |

. |

|

16 Tibia Clausa 97p |

16 8 |

8 4 2 8t 4t |

16 8 4 3 2 |

16 8 4 3 2 |

16 8 4 2 |

|

8 Clarinet 61p |

. |

8 8t |

16 8 |

. |

8 |

|

8 Saxophone 61p |

. |

8 |

16 8 |

16 8 |

16 8 |

|

8 Krumet 61p |

. |

8 |

8 |

. |

8 |

|

16 Solo String 85p |

16 8 |

8 4 |

16e 8 4 |

16 8 |

16 8 |

|

16 Solo String Cel. 85p |

16 8 |

8 4 |

16e 8 4 |

16 8 |

16 8 |

|

8 String 73p |

8 |

8 4 8te |

16 8 4 |

. |

8 |

|

8 String Celeste 73p |

8 |

8 4 8te |

16 8 4 |

. |

8 |

|

8 Viol d'Orchestre 73p |

8 |

8 4 8te |

16 8 4 2 |

. |

8 |

|

8 Viol Celeste 73p |

8 |

8 4 8te |

16 8 4 |

. |

8 |

|

16 Oboe Horn 73p |

16 8 |

8 |

16 8 |

. |

8 |

|

8 Quintadena 61p |

8 |

8 |

8 |

. |

8 |

|

8 Vox Humana 61p |

. |

8 4 |

16 8 4 |

16 8 |

16 8 |

|

8 Vox Humana 61p |

. |

8 4 |

16 8 4 |

16 8 |

16 8 |

|

16 Concert Flute 97p |

16 8 |

8 4 3 2 |

8 4 3 2 |

. |

. |

|

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

|

Piano (Wurlitzer grand) |

16 8 |

8 4 |

16 8 4 |

8 |

8 |

|

Harp |

. |

H |

H |

H? |

H? |

|

Master Xylophone |

. |

. |

X16 X |

X16 X |

X16 X |

|

Chrysoglott |

. |

C C4 |

C16 C |

C16 C |

C16 C |

|

Xylophone |

. |

X |

. |

. |

. |

|

Vibraphone |

. |

V |

V |

|

V |

|

Glockenspiel |

. |

. |

G |

G |

G |

|

Chimes |

. |

. |

C |

C |

C |

|

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

. |

|

Accomp to ... |

8 |

4 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

|

Great to ... |

8 |

8t |

16 |

8 |

. |

|

Bombarde to ... |

. |

8 |

. |

. |

. |

|

Solo to ... |

8 |

8 8p 8t |

16 8 8p |

16 8 |

16 |

Pedal: Bass Drum, Kettle

Drum, Cymbal, Chinese Gong

Accomp: Snare Drum, Tom tom, Tambourine, Castanets, Chinese Block, Sand Block

Great: Snare Drum, Tom tom, Tambourine, Castanets, Chinese Block, Sand Block

(Note: "3"= 2-2/3'; "e"= ensemble; "p"= pizzicato; "t"= 2nd touch)

The tuned percussions (except for the Chrysoglott) were located in their own chamber with its own expression.

(This stoplist appears in Jesse Crawford, Poet of the Organ; Wizard of the Mighty Wurlitzer, by John W. Landon. Additional information from Ray Thursby.) Condensation by Larry Chace.

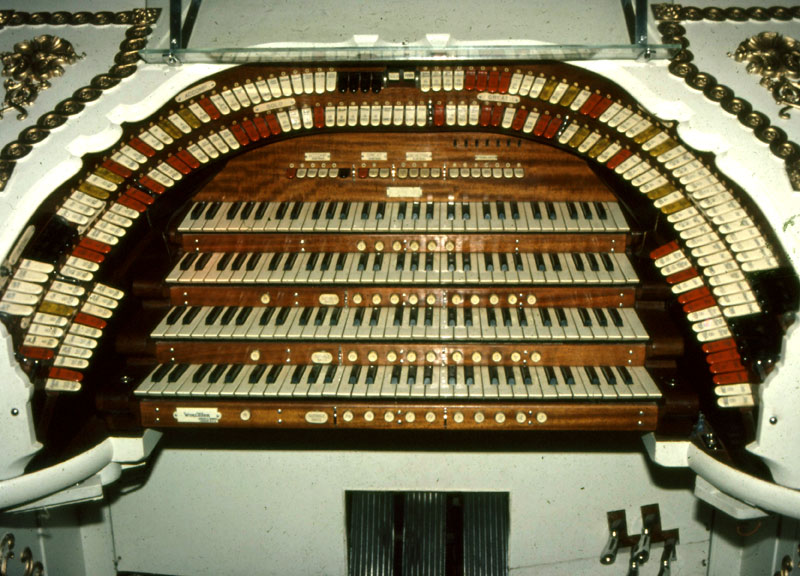

The instrument was arguably the best studio theatre organ in the USA in its day; folklore has it that it was a gift from the Wurlitzer Company to Jesse Crawford in recognition of the sales that had resulted from his endorsement of the Wurlitzer product and the inclusion of the words “recorded on the Wurlitzer organ” that graced the labels of all but his early Victor records (and nearly all those on HMV label overseas). It seems no longer possible to confirm this story, but the hearsay evidence supports it, including Jesse Crawford’s regret that he transferred ownership of the instrument during the 1940s to Paramount, as he was unable to provide a home for it (he owned no real estate in NYC), and subsequently reportedly searched in vain for a suitable pipe organ to record after the second World War. Be that as it may, the instrument was eventually put up for sale (by Paramount?) and purchased in the 1950s by Richard Loderhose, who installed it first in his home in Jamaica, Long Island, and then in 1975 the Bay Theatre, Seal Beach, California where it has achieved the size of 54 ranks (see http://www.baytheatre.com/). It was removed from the Bay Theatre in 2007 and is believed to be headed for a college auditorium in Arizona (as of August 2007).

In 1928, Howard Wurlitzer, whose tight financial control was evident throughout Wurlitzer’s history to that time, and who would have been most unlikely to sanction such a gift, retired, leaving the more pragmatic and generous Farny Wurlitzer in charge. It is believable that Farny would have approved such a gesture, and such evidence as exists does give credence to it.

It is to be assumed that Crawford had input into the instrument’s design. However, there is no record of how much influence he had, and it seems likely that, like the Paramount Theatre 4/36 organ, it was largely designed by the Wurlitzer team around some conceptual suggestions from Crawford. I have been unable to find any evidence to the contrary. One is inclined to wonder why it included only one Tibia Clausa, as the evidence of other organs subject to Crawford’s design influence suggests he would have specified two. That aside, it is a wonderful design for the microphone, with the bass extensions that would present the best characteristics for recording and wireless.

The studio is variously described as being located on the 9th or 10th floors of the Paramount Building in New York (the problem seems to derive from a mezzanine floor). Wherever it was, the studio well accommodated the sound of the Wurlitzer, which was provided with a skeleton “slave” console so that duets could be played by Jesse and Helen Crawford, a small number of which were issued on record; many more were performed on radio, and some examples of these can be heard on this website. A film released by Warner Brothers in 1936 features the Crawfords at two conjoined 3-manual skeleton consoles, and MAY have been recorded in the Paramount Studio.

Jesse Crawford recorded approximately seventy 78 r.p.m. record sides and four long-playing (by 1931 standards) records at the Paramount studio for Victor. Amongst these are to be found some of his very best recordings, and most of his best-known and loved interpretations of both contemporary popular song successes and more traditional fare. Below will be found links to all styles of these recordings.

Use of the organ was not confined to the Crawfords. Broadcasts by many other organists originated from the studio. Exactly what the arrangement was for Crawford’s organ to be used in this way, and indeed what accommodation was reached with Paramount to house the instrument, appears to have been lost in time. There appear to have been no significant problems, as no reports have been passed down to suggest that such existed. Although in the years up to 1933, at least, no other organist seems to have cut records at the studio, broadcasts were frequent and varied. Don Baker and perhaps others did make some 78s there before WW2, and others, including George Wright, made recordings there after the war.

In 1933, Jesse Crawford resigned from the position of organist at the Paramount Theatre, soon afterwards embarking on a tour of English theatres (see below). Shortly before he left, he recorded a final session for Victor, on 27/28 March, 1933. Some of these recordings were released soon afterwards; others were gradually released over the following three years. It would appear Victor released their final “new” Crawford recording in May, 1936. After his return from England, Crawford was to record at the Paramount Studio for Decca records, and also for Muzak and World Transcriptions. That stage in his career is covered in a separate section below.

It perhaps pertinent to point out that the depression and other contemporary social and economic influences had hit Victor hard. Sales of Victor records, which had peaked at 34½ million items in 1929, had fallen by more than 90% to just over 3 million at the nadir just three years later in 1932. It was not until 1940 that Victor’s sales once again exceeded 34 million. It is therefore understandable that organ recordings by Victor and others in the 1930s were largely solid-selling traditional semi-classical songs and ballad numbers that would not inherently contain what today would be called a “sell-by” date.

Crawford is shown at the console of the Paramount Theatre 4/36 Wurlitzer

A cropped version of the same photo serves a different purpose, testifying to Crawford's fame!

How About Me? - 12 January 1929 - Victor Master 48899 (first side cut in the Paramount Studio)

Me and the Man in the Moon - 13 January 1929 - Victor Master 48901-4

You're the Cream in My Coffee - 13 January 1929 - Victor Master 48902-3

Carolina Moon - 1 April 1929 - Victor Master 48950

A Precious Little Thing Called Love - 1 April 1929 - Victor Master 48951

I Love to Hear You Singing - 6 May 1929 - Victor Master 47990

Hawaiian Sandman - 6 May 1929 - Victor Master 47991

I've Got a Feeling I'm Falling - 7 May 1929 - Victor Master 47993 (with orchestra cond. Leonard Jay)

Tiptoe Through the Tulips - 4 December 1929 - Victor Master 56806

Chant of the Jungle - 4 December 1929 - Victor Master 56807

What is This Thing Called Love? - 11 February 1930 - Victor Master 56809

Rhapsody in Blue - 25 February 1930 - Victor Masters 56812/56813

It Happened in Monterey - 2 April 1930 - Victor Master 56817

Confessin' - 1 October 1930 - Victor Master 56863

So Beats My Heart For You - 30 September 1930 - Victor Master 56862

Cuban Love Song - 3 December 1931 - Victor Master 70964

Carolina's Calling Me - 16 December 1931 - Victor Master 70972

Music From The Student Prince - 24 May 1932 - Victor Long-Playing Record L-16010 (Serenade - Deep in My Heart - Students' March)

Schubertiana - 24 May 1932 - Victor Long-Playing Record L-16012 (Marche Militaire - Serenade - Moment Musicale - Unfinished Symphony - Song of Love)

Show Boat Medley - 25 October 1932 - Victor Long-Playing Record L-16014 (Ol' Man River - Make Believe - Can't Help Lovin' That Man - Why Do I Love You?) - vocals by Robert Simmons and Frances Longford

Melody in F - 26 October 1932 - Victor Long-Playing Record L-16020

"In 1931, RCA Victor developed and released the first 33⅓ rpm records to the public. These had the standard groove size identical to the contemporary 78rpm records, rather than the "microgroove" used in post-World War II 33⅓ "Long Play" records. The format was a commercial failure at the height of the Great Depression, partially because the records and playback equipment were expensive. The system was withdrawn from the market after about a year." Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RCA_Records

Pale Moon - 26 October 1932 - Victor Master 71775

The Song of Songs - 27 March 1933 - Victor Master 75580-1

L'Amour, Toujours L'Amour (Love Everlasting) - 28 March 1933 - Victor Master 75585-2. This was the final day on which Crawford recorded for Victor. Some recordings made 27/28 March 1933 were held in stock and released by Victor gradually over the next three years. The last of these appeared in May 1936.

Segments of three Royal Typewriter broadcasts featuring Jesse Crawford at the Paramount Studio in 1931 have survived. Restored versions of these may be heard. Each is approximately 14 minutes in duration.

6. Crawford's Organ Rolls

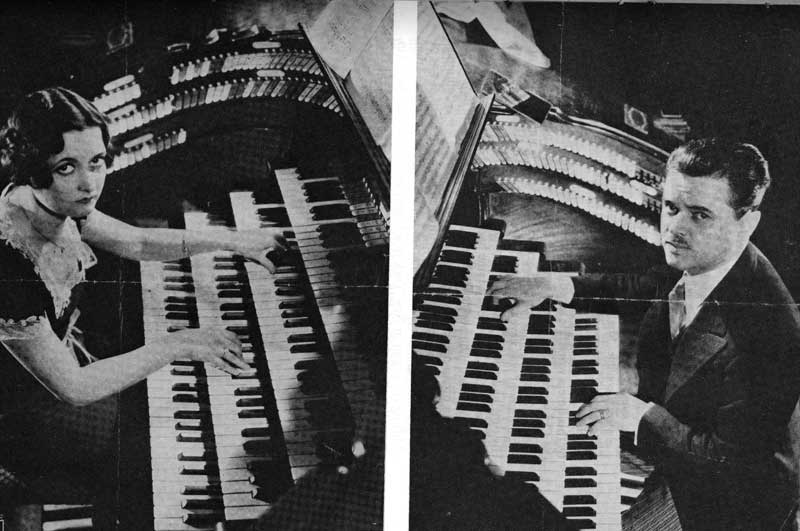

The console of the three-manual recording organ was set up in a showroom in the Wurlitzer factory that also housed residence and theatre horseshoe consoles

The Wurlitzer Company built a considerable number of organs for the homes of the wealthy, most of which clients were not able to play the organ. Like other builders of residence organs, Wurlitzer provided such instruments with automatic devices that enabled them to be played from paper rolls, on the same principle used in player pianos.

Various organists recorded performances on a special organ at the Wurlitzer factory. Crawford was no exception. He recorded over two dozen rolls, which enabled organs to reproduce not only the notes he played, but also the stops used and expression pedals. The "'R" rolls were able to control three manuals and up to thirteen separate ranks of pipes and some percussions. Alternative "RJ" or "Junior" rolls could control two manuals and seven pipe ranks with percussions.

Here are three of Crawford's rolls, played back on a Wurlitzer organ of almost identical specification to Wurlitzer's recording organ. All these rolls would have been recorded in around 1931.

Selections from "Monte Carlo": Beyond the Blue Horizon / Always in All Ways / Give Me a Moment Please / Beyond the Blue Horizon - Roll R-397

Baby's Birthday Party - Roll R-398

Selections from "The Love Parade": March of the Grenadiers / Nobody's Using It Now / Dream Lover / My Love Parade - Roll R-368

Unlike the other recordings on this website, these three tracks are from a double LP issued the organ enthusiasts' label Doric approximately 35 years ago, which as far as I am aware has not been reissued since. They are of significance for Crawford students not only through their clarity but because they contain repertory different from his 78s. In the event that anyone considers their copyright to have been infringed and objects to the presence of these tracks, please contact me so that they can be removed.

7. Crawford at the Empire Theatre, Leicester Square, London. 1933

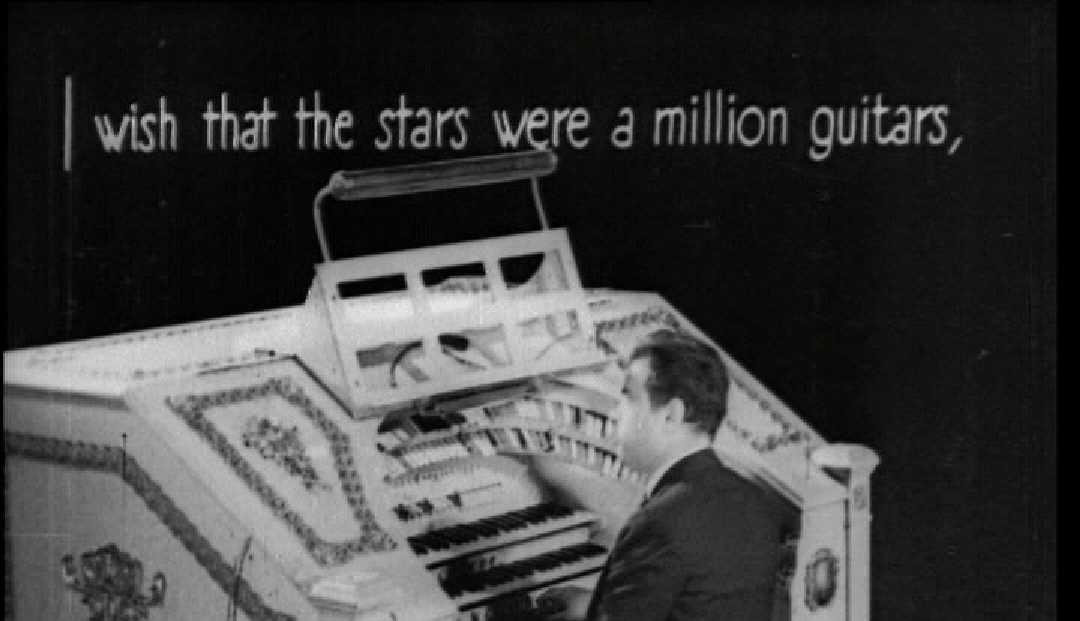

Crawford at the Empire, a frame from a film of him playing My Wishing Song. Photographs of Crawford actually playing are remarkably few.

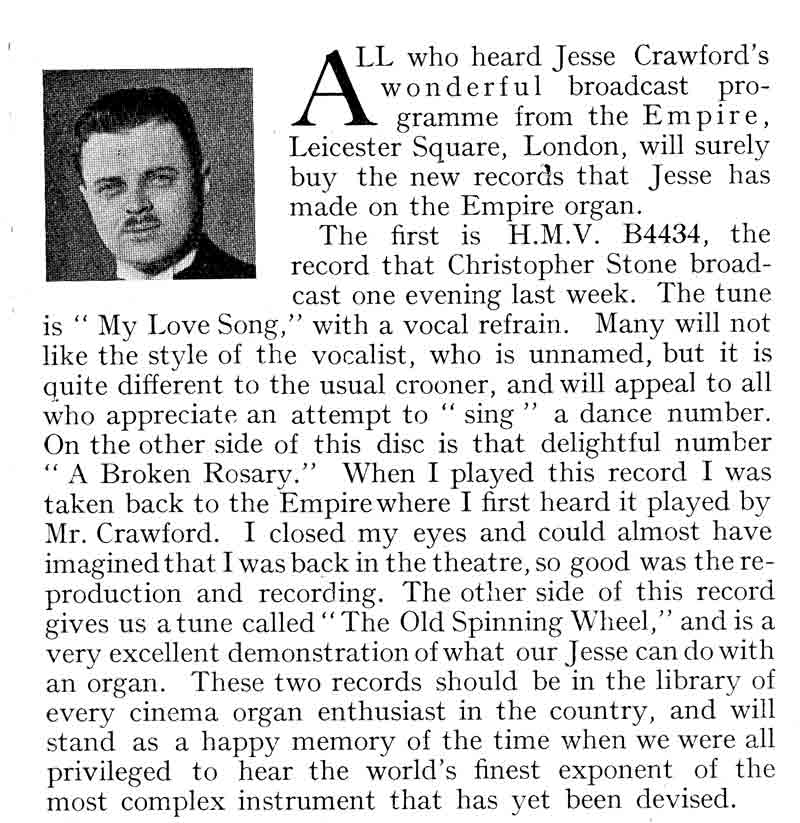

In 1933, Jesse Crawford resigned from the Paramount, New York, and embarked upon a tour of England, where he played at the Paramount Theatres in Manchester, Newcastle and Leeds and also the Empire, Leicester Square, London, where he appeared also on wireless, records and film, playing the 4/20 Wurlitzer organ. Although initially disconcerted by the single small microphone that was the entire equipment brought into the theatre auditorium, he was greatly impressed by the technical quality of the records that resulted, which he regarded as superior to the contemporary American product.

During his British tour, Crawford was interviewed on film at the Empire.

High resolution copies of the film may be obtained from http://www.britishpathe.com/index.php. Search for "Jesse Crawford"

Review of the first Crawford UK recording to be released (and the only one released in the USA). There appears to have been some editing of the text - no disc had three sides! It is clear that references to "My Wishing Song" that shared HMV4435 with "The Old Spinning Wheel" have been cut.

Cinema Organ Herald, May, 1933

A Broken Rosary - 1933 - Victor 24379A & HMV4434

My Love Song - 1933 (vocal - Jack Plant) - Victor 24379B & HMV4434

The Old Spinning Wheel - 1933 (vocal Jack Plant) - HMV4435

My Wishing Song – 1933 - HMV B4435

Hold Me - 1933 (vocal - Jack Plant) HMV B4460

Drifting Down the Shalimar – 1933 (vocal - Jack Plant) HMV B4460

In the Valley of the Moon - 1933 (vocal - Jack Plant) HMV B4461

Friends Once More - 1933 (vocal - Jack Plant) HMV B4461

Crawford's recordings were very popular in the UK. Even in 1938, five years after his visit and his last recording session for Victor (and only session for HMV), several of his records remained in the HMV catalogue, featuring an unannounced variety of instruments

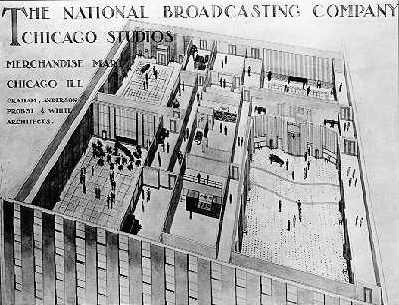

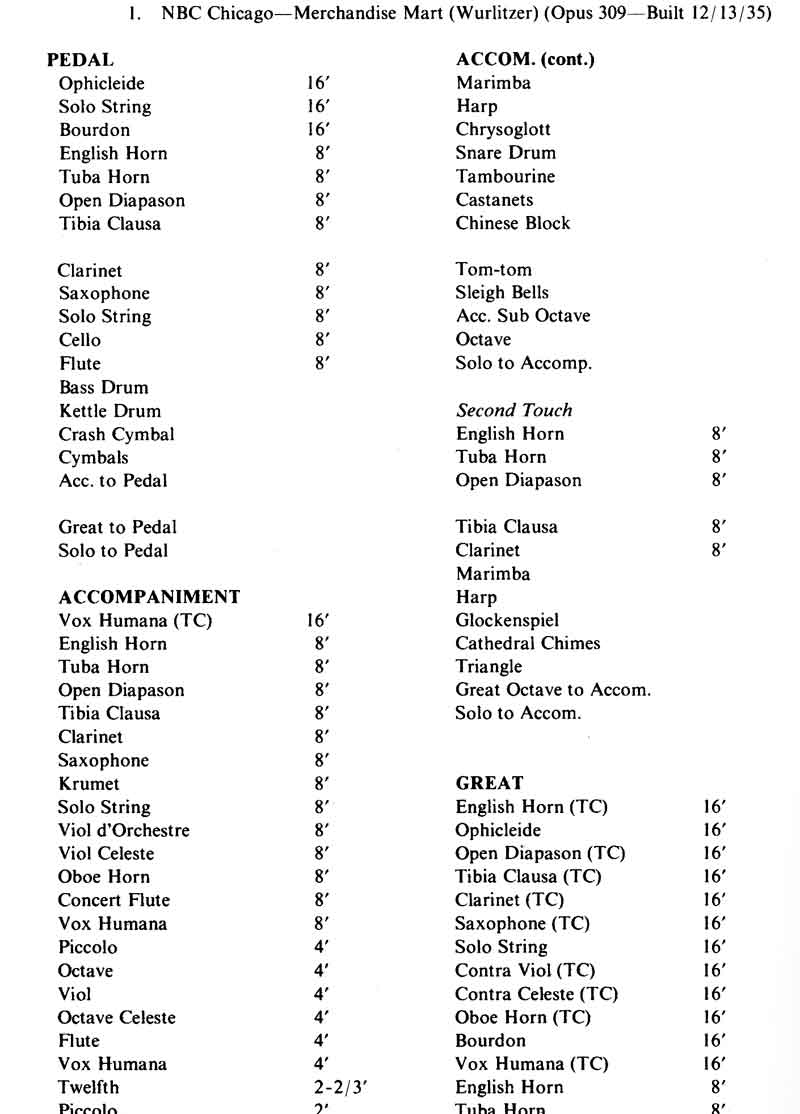

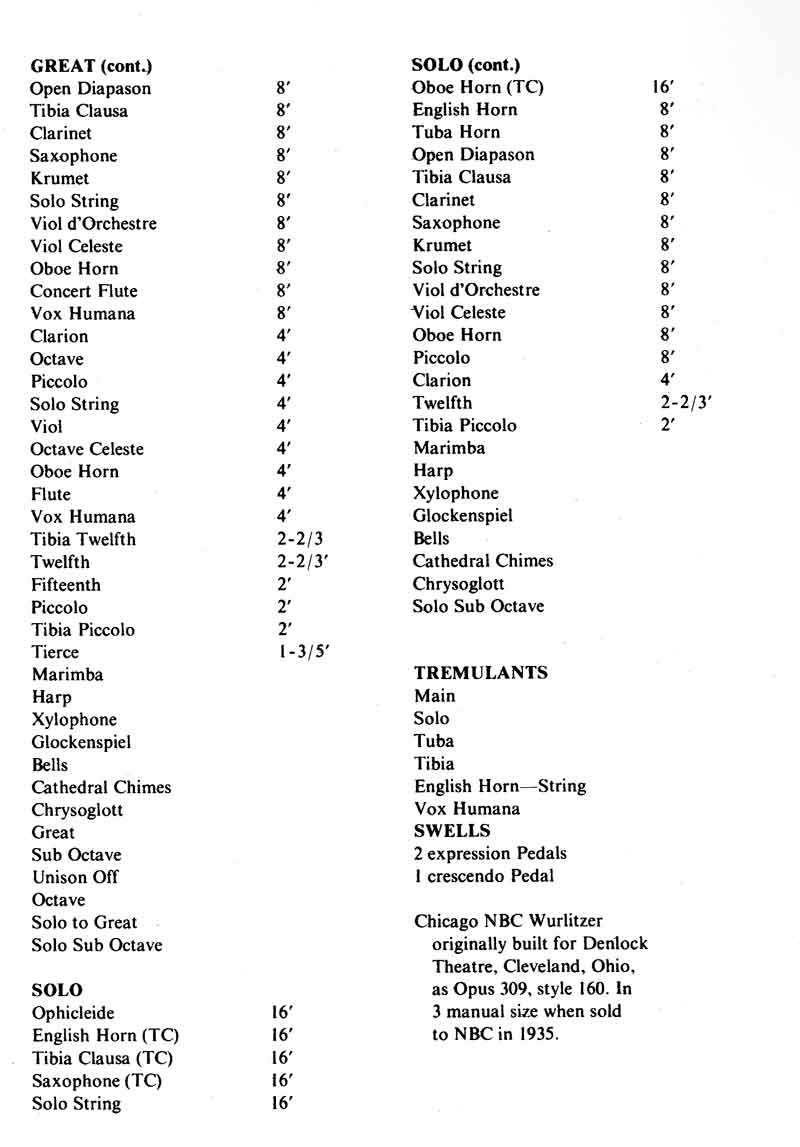

8. Crawford at NBC Chicago 1936

The Merchandise Mart, Chicago, Home of NBC

“Large enough to have its own ZIP code, 60654, the Merchandise Mart was designed by the Chicago architectural firm of Graham, Anderson, Probst and White to be a "city within a city". Second only to Holabird & Root in Chicago art deco architecture, the firm had a long-standing relationship with the Field family. Started in 1928, completed in 1931, and built in the same art deco style as the Chicago Board of Trade Building, its cost was reported as both $32 million and $38 million. The building was the largest in the world in terms of floor space, but was surpassed by The Pentagon in 1943, and now stands sixth on the list of largest buildings in the world. Once the largest commercial space in the world, the Aalsmeer Flower Auction is now recognized by Guinness World Records as holding the record.”

…

“Before the location even opened, NBC announced plans to build studios in the Mart. When opened on October 20th, 1930, the twentieth floor location covered 65,000 square feet and supported a variety of live broadcasts including those requiring orchestras. WENR and WMAQ broadcast from the location. Expanded in 1935, with office space in the previously unoccupied tower, the additional 11,500 square feet provided room for an organ chamber, two echo rooms, and a total of 11 studios. A staff of more than 300 produced up to 1,700 programs each month including Amos 'n' Andy.” Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/?title=Merchandise_Mart

The studios prior to 1935 - Floors 19/20

“NILES TRAMMELL, vice-president and manager of the NBC central division, announced addition of three new studios to the Chicago headquarters. An organ chamber, two echo rooms and additional office space, occupying about 11,5000 square feet of floor space, will be constructed in previously unoccupied space in the tower section of the Merchandise Mart. This will give the Chicago NBC headquarters a total of 76,500 square feet of floor space, and 11 studios. When the Chicago headquarters were opened in 1928 only two studios were needed and the entire staff was limited to less than a dozen people. Today's staff numbers more than 300. Of the 1,748 programs originating each month for a total of 536 hours, 1,102 are for the networks. Each of the new studios will be 17 by 30 feet in size with an adjoining control room and adjoining storage room.” Broadcasting magazine, 15 September, 1935

“Studio G housed the organ console (the pipes were located in an adjacent space). The organ saw plenty of use in the glory days of the soap operas, though the actors were very often working out of another studio. (Some soaps used a Hammond organ which was generally in studio H). The card table in the foreground was presumably for an organist working "standby" duty as mandated by NBC's contract with the American Federation of Musicians. In case of unforseen program interruptions, she/he could leap to the console and play until notified by the Master Control engineer that the trouble had been rectified.” http://198.173.117.4/nbcmm/facilities/studiog.html

Inaugural NBC Broadcast - 1 March 1936 Note: This is a large file (24MB) so please be patient!

9. Crawford returns to the Paramount Studio, New York 1934 -1942

When he returned from England, Crawford did not immediately resume recording. It was in approximately 1934 that his association with Decca Records began, and was to continue intermittently for over twenty years (far longer than the Victor association that lasted from late 1924 until Spring, 1933 (about 8½ years)) but encompassed the transition from 78s to LP records.

However, at least in the 78 days that concern us here, the Decca recordings generally were far less exciting than those he had made for Victor, and show little of the rhythmic and registrational dexterity that gave charm to so many of his Victor recordings. The choice of repertory was pedestrian and gave him few chances to shine. A limited number of these recordings is included for historical reasons.

In the late 1930s, Crawford began to make increasing use of Hammond organs, both for their convenience and because many of the theatre organs on which he used to perform had fallen into disrepair, if not total disuse. The Paramount Studio Wurlitzer remained available and was used for radio and for the recording of transcriptions, which continued until sometime in the mid-1940s.

Some records were issued of him playing Hammond organ, but it was not until the 1950s that such records became the norm for him. He was not able to find a pipe organ that he considered suitable, and is understood to have expressed regret that he had parted company with the Paramount Studio Wurlitzer when the studio was taken over for war purposes (the organ remained there, but was not for some years accessible for broadcasting or recording. Later, as we know, he discovered the Robert Morton organ in Lorin Whitney’s California studio and made several LP recordings on it for Decca. His final two albums were made at Richard Simonton’s Toluca Lake home using the 4/36 Wurlitzer the pair had designed.

Our survey covers the period up to the time Crawford stopped using the Paramount Studio organ, and it can be seen that by this time Crawford’s style had begun to change towards the more harmonically complex arrangements that were to typify his later LP recordings. He undertook formal studies with Joseph Shillinger (1895-1943), and some of the results of those studies can be heard in his final recordings for World and Muzak at the Paramount Studio. In particular, the harmonies he uses in Swinging Down the Lane and the wailing lacrimosity of A Cottage for Sale show how much his style was changing.

Decca Records

Kiss Me Again - 10 September 1934 - Decca record 178B - Master C9453

When the Organ Played at Twilight - 8 May 1941 - Decca record 3923A - Master 69147

The Perfect Song - 8 May 1941 - Decca record 3923B - Master 69170

NBC Broadcasts

Broadcast - 13 September 1938 (NBC)

Broadcast - 14September 1938 (NBC)

Broadcast - 16 May 1939 (NBC)

Muzak Transcriptions

Easter Parade - 20 March 1941

A Pretty Girl is Like a Melody - 20 March 1941

Lovely to Look At - 20 March 1941

Look for the Silver Lining - 20 March 1941

My Blue Heaven - 27 March 1941

I Want to Be Happy - 27 March 1941

If I Love Again - 27 March 1941

World Transcriptions (1940-42)

10. Jesse Crawford at the Hammond Organ

NBC Television show (soundtrack) - 9 February 1949

I should like to acknowledge the kindness and generosity of Dr John Landon who made available to me his complete collection of all known recordings by Mr and Mrs Crawford, from which it has been my great pleasure to select the above examples of their playing for restoration so that they can be studied and appreciated.

Those wishing to learn more about the lives and music of this outstanding husband and wife team are strongly recommended to read John's comprehensive biographical work Jesse Crawford, Poet of the Organ, Wizard of the Mighty Wurlitzer - Vestal Press, Vestal, New York, 1974 - ISBN 0-911572-11-2.

Thanks are also due to Ray Thursby, who provided valuable information about the Paramount Studio organ, and to several members of the Theatreorgans-L discussion list who endangered their eyesight identifying the Chicago Theatre as the organ shown in the 1925 Victor record catalogue. Chris Wesson's helpful comments regarding my early experiments in restoration of theatre organ 78s have also contributed to whatever success I am considered to have achieved.

Links:

Short Study Note in the Virtual Radiogram

An online biography of Jesse Crawford

George Wright's Reminiscences of Jesse Crawford

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

If you have any thoughts about the Crawfords and/or these recordings, please use my guest book to share them. Responses may take a while, as I shall very shortly be overseas for some weeks, and am frequently away for extended periods.

Sign

My Guestbook ![]() View

My Guestbook

View

My Guestbook

Return to the Virtual Radiogram